How do the Conservative and Labour manifestos measure up in terms of health inequalities?

The manifestos have been published, but what are they likely to mean for health and care inequalities? Let’s take a closer look and examine the underlying evidence.

Labour manifesto – shows promise but needs investment

Labour has committed to reducing inequalities in healthy life expectancy between regions by half and highlighted the need for action on the social determinants of health. Decades of evidence has shown that health is driven by social factors rather than health care. (1)

The planned strategy to address childhood poverty is much needed considering we have 3.6 million children living in poverty, (2) but details are light. Action on smoking, (3) obesity, (4) mental health, (5) HIV, (6) and harmful gambling (7) is also welcome as these issues go hand-in-hand with poverty and disadvantage. There are also ambitions to address inequalities in maternal mortality. The cross-cutting theme of community-developed solutions with faith groups and voluntary and community sector enterprises is positive and supported by the evidence. (8)

For primary care, there are trials of Neighbourhood Health Centres, which sound similar to Integrated Neighbourhood Teams. (9) Integrated care has the potential to improve patient experience and reduce inequalities (10) because it reduces the amount of effort or agency needed by patients to get the care they need. They could go further to also include voluntary and community organisations, social workers, and geriatricians. The manifesto also alludes to financially incentivised continuity of care, which if designed equitably is likely to benefit the most disadvantaged groups. (11)

However, the details about how these targets will be achieved are sparse – both in terms of specific actions on the social determinants of health and what the targets mean. For example, reducing inequalities between large geographic regions compared to small areas is more achievable but less impactful. Additional short and medium term targets are likely to be needed to compliment this goal, such as infant mortality, obesity, mental health and suicide. (12)

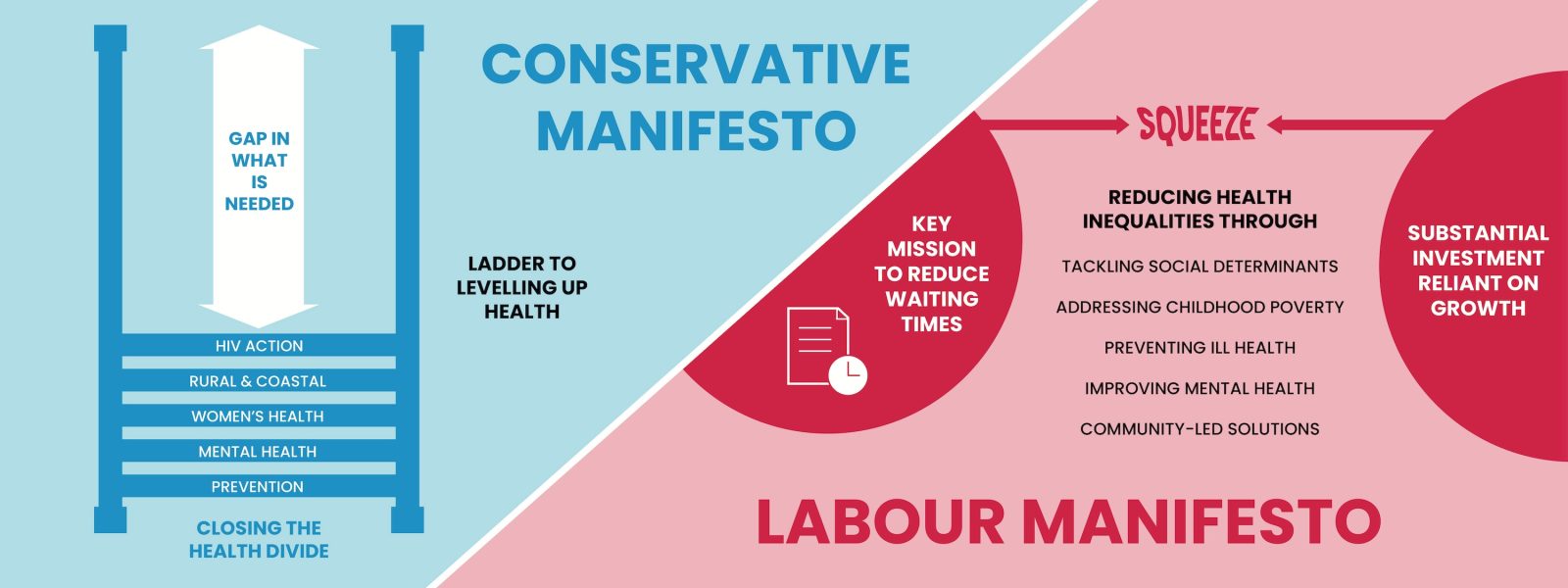

Despite much to be commended in the manifesto, there are two major concerns. First, the headline health mission is focused on reducing waiting lists, which may squeeze local action on prevention, social determinants of health, and inequalities. Second, without a cash injection into the NHS and public health, it is difficult to see how struggling health care organisations and local authorities are going to look beyond the immediate priorities of simply keeping healthcare services functioning.

Conservative manifesto – tweaks around the edges are unlikely to shift the dial

Several of the announced policies in the Conservative manifesto may have positive impacts on population health. For example, the Tobacco and Vaping Bill could have substantial benefits over the long term and so would reducing advertising of unhealthy foods as part of action against obesity. Smoking and obesity have a strong socio-economic gradient (3,4) and therefore such policies are likely to benefit lower socio-economic groups more. However, the manifesto does not set out any ambitions to equalise health or care beyond that. Policies on women’s health, (13) mental health, (5) and HIV (6) are welcome but will benefit the most disadvantaged communities only if an inequality angle is integrated in the delivery. Similarly, investing proportionately more in out-of-hospital services may help to strengthen and standardise care closer to home. However, an inequality angle is again required to ensure that the gap in primary and community services does not widen especially where resources are constrained. Addressing the unique health and care needs of rural and coastal communities (14) features and has the potential to narrow inequalities within and between regions but this will happen only if the benefits reach the most disadvantaged within these communities.

Similar to the Labour manifesto, the Conservatives promote more patient choice, which is likely to increase inequalities because more affluent groups are likely to benefit more. (15) In the Conservative manifesto there is an increase and widening of the Immigration Health Surcharge and a requirement for some people coming to the UK to purchase health insurance. These measures are likely to worsen the health of migrants, and particularly those on low incomes. (16) Finally, a reduction in NHS managers, as described in the manifesto, is likely to make efforts to address inequalities in the NHS more difficult (17) because action on inequalities takes coordination and targeting of services.

So, what’s the conclusion?

Manifestos are a pitch to the public to win votes; they usually over-promise and under-deliver. Governing is different from campaigning. The Labour manifesto shows promise in addressing inequalities but may be difficult to deliver in the short to medium term without substantial investment in the NHS and public health or a fundamental reallocation of resources. There are few positives to address inequalities in the Conservative manifesto, but these amount to tweaks around the edges rather than a step change in levelling up health across the country.

Neither manifesto clearly articulates a bold and ambitious plan to transform health and care, notwithstanding the Tobacco and Vaping Bill. Economic growth and productivity are priorities in both manifestos; both require a healthy and thriving workforce. (18) Extended sick leave because of NHS delays or an unhealthy population due to poor diet or damp housing is not going to facilitate economic growth. Equally economic growth not equitably shared is not going to facilitate a healthier society. (19) There are plans to improve mental health services to help working age people (both Labour and Conservatives) and reform fit notes (Conservatives), but little mention of the need to support musculoskeletal health in working age.

There is no quick fix to improve the health of the public, build efficient health care services and reduce inequalities. Instead, it requires long-term, cross-government, and multi-agency action. (8) Any change in government presents an opportunity to re-think our direction. The wide inequalities in health and care across our society are not inevitable but require bold political choices.

References

1. Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden A, Wright K, Whitehead M, Petticrew M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2010 Apr 1;64(4):284–91.

2. Francis-Devine B. Poverty in the UK: statistics. 2024 Jun 14 [cited 2024 Jun 14]; Available from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn07096/

3. Action on Smoking and Health. Health Inequalities and Smoking [Internet]. Action on Smokng and Health; 2019 Sep [cited 2024 Apr 24]. Available from: https://ash.org.uk/uploads/ASH-Briefing_Health-Inequalities.pdf#page=1.25

4. Mayor S. Socioeconomic disadvantage is linked to obesity across generations, UK study finds. BMJ. 2017 Jan 11;356:j163.

5. Waterall J. Health matters: preventing cardiovascular disease. Public Health Matters Public Health England. 2019;

6. Lewer D, Jayatunga W, Aldridge RW, Edge C, Marmot M, Story A, et al. Premature mortality attributable to socioeconomic inequality in England between 2003 and 2018: an observational study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020 Jan 1;5(1):e33–41.

7. GOV.UK [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Gambling-related harms evidence review: summary. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review-summary–2

8. Davey F, McGowan V, Birch J, Kuhn I, Lahiri A, Gkiouleka A, et al. Levelling up health: a practical, evidence-based framework for reducing health inequalities. Public Health in Practice. 2022;4:100322.

9. Nuffield Trust [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Integrated neighbourhood teams: lessons from a decade of integration. Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/integrated-neighbourhood-teams-lessons-from-a-decade-of-integration

10. Gkiouleka A, Wong G, Sowden S, Bambra C, Siersbaek R, Manji S, et al. Reducing health inequalities through general practice. The Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(6):e463–72.

11. Tarrant C, Windridge K, Baker R, Freeman G, Boulton M. ‘Falling through gaps’: primary care patients’ accounts of breakdowns in experienced continuity of care. Family Practice. 2015 Feb 1;32(1):82–7.

12. Targeting health inequalities – realising the potential of targets in addressing health inequalities – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/targeting-health-inequalities-realising-the-potential-of-targets-in-addressing-health-inequalities

13. Winchester N. Women’s health outcomes: Is there a gender gap? 2021 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Jun 14]; Available from: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/womens-health-outcomes-is-there-a-gender-gap/

14. GOV.UK [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Chief Medical Officer’s annual report 2023: health in an ageing society. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annual-report-2023-health-in-an-ageing-society

15. White M, Adams J, Heywood P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? In: Social inequality and public health [Internet]. Policy Press; 2009 [cited 2024 Jun 14]. p. 65–82. Available from: https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/edcollchap/book/9781847423221/ch005.xml

16. NHS charging for maternity care in England: Its impact on migrant women – Rayah Feldman, 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0261018320950168

17. In defence of NHS managers: a response to the Conservative plan to cut 5,500 posts – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/in-defence-of-nhs-managers-a-response-to-the-conservative-plan-to-cut-5500-posts

18. Our society won’t thrive without a healthier workforce – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/our-society-won-t-thrive-without-a-healthier-workforce

19. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 14]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on