What works: How health care organisations can reduce inequalities in social determinants of health in their role as anchor institutions

Health care organisations can mitigate social and health inequalities by offering high-quality, equitable care. They can also improve communities’ overall wellbeing through their influence and assets to improve the economic, social, and environmental conditions in local areas. In this brief, we review academic papers on how health care organisations can effectively operate as anchor institutions to address inequalities in social determinants of health.

What works – anchor institutions[PDF 254kb]

Download documentSummary

Health care organisations can mitigate social and health inequalities by offering high-quality, equitable care. They can also improve communities’ overall wellbeing by using their influence and assets to improve the economic, social, and environmental conditions in the areas they serve, acting as anchor institutions. This way they can reduce inequalities in the social determinants of health and contribute to healthier and thriving communities.

In this brief, we reviewed 25 academic papers on how health care organisations can effectively operate as anchor institutions to address inequalities in social determinants of health. Papers were identified through a Medline search and snowballing. They included case studies (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), reviews and theoretical pieces.

The reviewed literature suggests that health care organisations can reduce inequalities in social determinants of health for their local communities through their role as anchor institutions by:

- Working with local partners to achieve health equity.

- Purchasing locally from a diverse supply chain.

- Providing quality jobs and promoting workforce development and leadership.

- Transforming organisational spaces into community assets.

Current challenges

Anchor institutions: Large organisations rooted in specific areas and communities, using substantial resources to address social needs and enhance community wellbeing [1][2][3]. Examples of anchor institutions include NHS Trusts, local authorities and universities [4].

Our health is shaped by the conditions we are born into, grow up in, live, and work in – what we call social determinants of health [5]. Inequalities in determinants like housing, income, working conditions, and access to health promoting environments drive health inequalities across different groups. Health care organisations can mitigate these inequalities by offering high-quality, equitable care. But beyond that, they can also improve communities’ overall wellbeing by using their influence and assets to improve the economic, social, and environmental conditions in the areas they serve [2].

Employing more than 1.36 million people, the NHS is the largest employer in the country [6][7]. It controls a budget that in 2022/23 exceeded £150 billion [8] and its estates portfolio covers broadly 6,500 hectares of land [9]. Due to the size of its assets and its long-lasting presence in local geographical areas, the NHS and its organisations are understood as anchor institutions.

Decisions made within anchor institutions have significant effects on local economies and environments. They have the potential to drive prosperity and reduce inequalities in social determinants of health, especially in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. Their potential lies in contributing to inclusive employment opportunities, economic growth, and healthier physical and built environments [2].

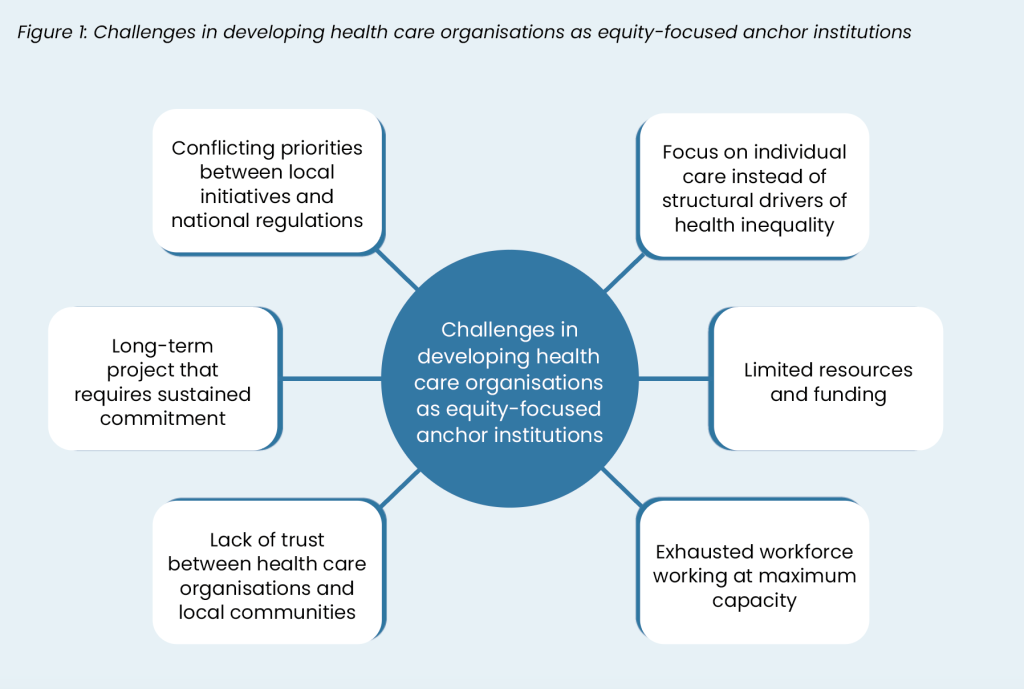

However, developing a successful anchor activity strategy that addresses local inequalities in social determinants of health is challenging. Health care organisations and their employees often centre their responsibilities on individual patient care, access to that care and proximate socioeconomic factors [10]. When it comes to addressing health inequalities, they are more likely to focus on aspects of service delivery rather than the structural drivers of inequalities [11]. Shifting this focus towards adopting an anchor responsibility can often be met with resistance among staff. This is particularly relevant in situations where resources and capital funding are constrained, local initiatives encounter challenges posed by national regulations, and the workforce operates at maximum capacity [12].

Short-term approaches in recruitment and sourcing staff from outside the local area targeted to meet the immediate needs of organisations can hinder the creation of inclusive employment opportunities [13]. Further, lack of trust between health care organisations and disadvantaged communities makes it difficult for organisations to engage with local populations, understand their needs and co-create solutions within their anchor activity strategy [12]. Contributing to inclusive labour markets, economic growth, and thriving communities are long-term projects and relate with a diverse range of socioeconomic, relational, and health outcomes. Engaging people in action in a sustainable manner can be difficult when they cannot see the immediate outcomes of their efforts. This adds an additional challenge in developing an equitable and sustainable anchor activity strategy [1].

In the current context of widening social and health inequalities and required health care reforms, unlocking the potential of health care organisations as anchor institutions is attracting increasing attention from health care providers, public health experts and state leadership [4][14][15]. However, we are still building a consensus around how this can be achieved in an equitable manner. In this brief, we review academic literature on the most effective ways that health care organisations can maximise their local impact as anchor institutions and reduce inequalities in social determinants of health.

Summary of evidence

We reviewed 25 academic papers on how health care organisations can effectively operate as anchor institutions to address inequalities in social determinants of health. Papers were identified through a Medline search and snowballing. They included case studies (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), reviews and theoretical pieces.

The reviewed literature suggests that health care organisations can reduce inequalities in social determinants of health through their anchor activity by:

- Working with local partners to achieve health equity

- Purchasing locally from a diverse supply chain

- Providing quality jobs and promoting workforce development and leadership

- Transforming organisational spaces into community assets

1. Working with local partners to achieve health equity

Healthcare organisations should adopt an equity- focused strategy for their anchor activities to reduce local social and health inequalities.Evidence suggests that improving social determinants of health should be part of organisations’ missions, as anchor projects alone may not achieve this impact [1][16]. Almost all studies highlight that to achieve this mission, anchor activities need to be co-developed and implemented within local partnership networks (e.g., the NHS Greater Manchester Anchors Network). A recent UK study showed that place-based mutual partnerships with other anchor organisations (e.g., universities, local authorities) and experienced community engagement actors (e.g., faith or social enterprise organisations) create a context of trust which enables the co-creation of anchor projects. This in turn widens the participation of local communities in anchor projects and maximises their reach [17].

However, a US study has shown that communities can be sceptical or even resistant towards hospital or health care organisations having a mission other than providing health care [18]. Many of the study participants (total n=35) were unaware that the hospital was involved in community development activities. When they learned about it, they raised concerns about the hospital potentially accelerating gentrification. Engaging communities and establishing trustful partnerships requires time and effort. According to a review of 13 articles [19], there are three key elements in building such partnerships:

- Asking employees living in the local areas to identify agents like faith communities, local governments, schools who can be trustedand proactive partners.

- Entering partnerships with transparency about own organisation’s values, mission, and capacity and with a ‘humble attitude’ that allows for mutually respectful relationships.

- Understanding what community members value as important factors of trust, e.g., communication, credibility or resolution of

Working with community partners to achieve health equity expands beyond the walls of health care organisations. For example, hospital leadership can actively advocate for and contribute to policy discussions about regional transportation plans and zoning policies to promote transit connectivity and affordable housing [20]. Additional examples from the US include health care organisations advocating against structural inequity like in the case of the John Hopkins academic medical centre [21]. The Centre, in cooperation with John Hopkins University, created a series of webinars and a symposium to address violence and racialinjustice. Their innovation was that they engaged the community surrounding the Centre and co-created suggestions for violence prevention [21].

During the pandemic, many health care organisations intensified their efforts to engage with communities [22][23]. In particular, academic hospitals undertook a leadership role in advising and educating communities around best practices, assessing population needs, and educating students around the impact of the social determinants and community engagement [24][25] [26]. Lessons learned during the pandemic can be applied in non-emergency times as well [25].

2. Purchasing locally from a diverse supply chain

Literature from both the UK and the US stress that when health care systems and organisations purchase goods and services from diverse local suppliers, they contribute to inclusive economic growth and community wealth building [3][27].

However, purchasing locally is challenging especially when – like in the UK – national procurement frameworks and regulations complicate budget management. A study in a UK health care provider found that poor IT support or skills, inconsistent electronic purchasing and inventory management, inefficient approval systems, and disorganised environments impacted procurement decisions [28]. To overcome these challenges, employees used various strategies like relying on internal and supplier relationships, bypassing procedures, and purchasing outside of agreements to reduce cost. In such cases, purchasing from local diverse suppliers requires simplified procurement procedures, optimised electronic systems, and IT training for staff. It further requires including ‘local presence’ in supplier selection criteria and giving local suppliers the chance to connect with organisation staff.

A series of realist-informed case studies [17] showed that health care organisations can increase the amounts they spend locally based on an equity-focused strategy that involves:

- Knowledge of the local market for the identification of local suppliers and opportunities, g., setting up childcare schemes for hospital employees using local service providers.

- Enabling local suppliers to join supply chains through training (e.g., on how a local business can bid for an NHS contract), simplified and accessible forms, and encouraging collective

However, to reduce local income inequalities, spending needs to be channelled with an intention to reach those experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage [16]. The Supplier Development Programme in Glasgow is a useful example of how this can be done in practice [29]. The programme focused on increasing diversity within the NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Supply Chain. It encouraged businesses led by, for,and with people with protected characteristics as defined by the Equalities Act Scotland & Fairer Scotland Duty, to work with them. The organisers delivered free tender training webinars and provided guidance, tools, and expert resources to invited businesses with an emphasis on those owned or led by women, minority, disabled, and LGBTQ+ individuals.

Almost 64% of the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that attended the engagement and training events identified as being 50% or more owned or led by individuals with protected characteristics. Among the people who gave feedback on the project, 81% said they were more likely to bid for future public contracts as a directresult of participating in the programme [29]. This example demonstrates that targeted interventions can change the longer-term supply chain patterns of the NHS.

3. Providing quality jobs and promoting workforce development and leadership

Health care organisations can transform the socioeconomic wellbeing of their local communities by maximising their impact as employers. Similar to purchasing locally, hiring people living in disadvantaged local areas requires an intentional strategy [30]. First, health care organisations need to establish themselves locally as attractive employers. Often, people are not aware of the multiple job roles that are available in hospitals or other health care settings beyond doctors, nurses and paramedics [18]. Effective ways to increase organisations’ visibility as employers include:

- using workforce ambassadors

- hosting job fairs in community venues

- working with schools and universities to promote opportunities and preparatory training programmes [17].

Second, organisations need to enable the participation of disadvantaged groups in job recruitment processes. Evidence highlights that flexible recruitment pathways away from traditional application forms and shortlisting are key for widening participation of disadvantaged communities in the health care workforce [17].

Useful examples highlighted in the literature [17][27][31] included:

- in-person events like job fairs in accessible community venues

- opportunities for direct contacts between community members and organisation staff, e.g., through open days

- quick start to the job through simplified paperwork and support (e.g., for the collection of documents)

- removal of requirements to divulge information about criminal history at the initial stages of employment

‘Ban the Box’ programme: This campaign refers to the removal of the box that asks about criminal history on an application [27]. The ‘Ban the Box’ campaign for inclusive employment is currently running in the UK and aims to make 2 million jobs more inclusive for all disadvantaged jobseekers by 2025 [31]. Almost 35% of the employers participating in the scheme believe that the programme has addressed the skills shortages in their business [32].

Other initiatives that can widen participation of disadvantaged communities in the health care organisation workforce involve job placement programmes or apprenticeships for young people. Such programmes can give a chance to individuals unfamiliar with health care settings to gain insight, and develop knowledge and skills needed by the organisation [1]. For example, the Dorset County Hospital Foundation Trust in the UK [33], used the Kickstart scheme to offer job placements to young people at risk of long-term unemployment and disengagement. Almost 80% of the 35 people on placement were subsequently recruited into permanent roles [33].

The Kickstart Scheme: A programme implemented during the pandemic to provide funding for job placements for 16–24-year-olds on universal credit who are at risk of long-term unemployment and disengagement [36].

Third, organisations need to provide good employment conditions, e.g., through living wage policies, opportunities for skills development,career progression, and leadership [2][16][34]. A UK study highlights that especially for new employees from local disadvantaged areas, providing ongoing and co-ordinated support at least during the first months of employment, enables people to manage challenges and boosts their confidence. At the same time a culture of mutual respect is cultivated in the organisation which is beneficial for everybody [17]. The same study shows that when individuals in senior leadership have lived experienced of socioeconomic disadvantage, they appreciate the importance of strengthening communities. In turn, this translates into supporting anchor activity initiatives across the organisation [17]. Findings like this highlight that improving diversity in workforce and widening access to leadership positions should not be seen solely as a desirable outcome of effective anchor activity. It is also a wayto make NHS organisations effective anchor institutions.

Anchor institutions rely on all staff taking a proactive approach to identifying opportunities for interventions and strengthening community links. For example, a US article discusses the important role nurses can play in building networks that promote communitywellbeing because they are a trusted profession with experience in collaboration with diverse stakeholders [30]. Healthcare organisations need to enable leaders across all seniority levels to identify needs, opportunities and assets, and act. The ‘Learning to lead together in Newcastle’ scheme is a good example of how leadership training can bring together health care organisations, local authorities and the voluntary sector [35]. The scheme enables participants to learn from each other and employ a system approach in addressing challenges in the broader Newcastle area. Since 2019, more than 200 people have graduated from the scheme, including finance directors, clinicians, GPs, charity leaders and pharmacists. Most of them find that the training has significantly helped them to fulfil their roles and advance their system-thinking.

4. Transforming organisational spaces into community assets

A report by the Health Foundation highlighted the importance of leveraging the physical assets of the NHS for community benefit [2]. Thereport described four main components of anchor capital strategies:

- Enabling local groups and businesses to use NHS estates.

- Supporting access to affordable housing or housing for key workers using NHS estate.

- Working in partnership across a place to maximise the wider value of NHS.

- Developing accessible community green.

Recent case studies in disadvantaged areas of England highlight these components in detail, such as NHS trusts hosting affordable food markets or local charities on hospital premises, opening trusts’ green spaces for members of the public, and integrating green spaces into broader plans of ‘green corridors’ in cities [17]. The case studies also point to the importance of communication with communities for the right use of organisations’ assets. Organisations can open their doors to communities, but they should first understand local needs and collaborate with partners to facilitate the use of open spaces.

Regarding affordable housing, there have been suggestions regarding releasing or selling NHS land for building new houses for staff but also for local people [37][38]. However, ownership and control of NHS estates is complex and there are limited examples of anchor activity on the use of estates in the UK [2]. However, Bon Secours Hospital’s Affordable Housing Program is a useful example coming from the US [39]. In the 1990s, noticing rising vacant homes in Baltimore, Bon Secours seized the opportunity to buy and develop them into affordable housing [40]. As of 2019, Bon Secours owned 801 affordable housing units across 12 West Baltimore properties for low-income residents, including families, seniors, and people with disabilities. A social-return-on-investment analysis showed the significant social value of the affordable housing program, generating between $1.30 and $1.92 of social return in the community for every dollar in yearly operating costs [39].

Thinking differently about how the NHS can leverage its assets for the benefit of local communities is currently very relevant. The recent report on the state of the NHS in England [41] recommends urgent capital investments in modern buildings and the strengthening of processes around capital approvals. It is crucial that any actions from these recommendations align with the NHS vision as an anchor institution, leveraging opportunities for local employment and transforming spaces into community assets. The same applies for the NHS commitment to deliver a ‘net zero’ health service in the next twenty years [42]. Keeping this commitment requires the transformation of buildings, technologies, and environments and any relevant plan should be informed by NHS broader vision to serve its communities [17][43].

Limitations

This evidence brief provides an overview of the existing literature on health care organisations as anchor institutions. The main limitation concerns the fact that most studies offer qualitative evidence which does not offer insights to measurable and comparable impacts of anchor activities on social determinants of health or health outcomes.

What works: key recommendations

| Recommendation | Target audience | GRADE certainty |

|

Adopt achieving health equity as part of the organisation’s mission.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Increase the organisation’s participation in place-based partnerships and collaboratives and engage in mutually respectful, reciprocal relationships with communities.

|

Trusts and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Foster the organisation’s public image as an economic player, attractive employer and advocate for health equity.

|

Trusts and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Ask employees who live in the local area to identify trusted and proactive anchor activity partners.

|

Trusts and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Increase the organisation’s knowledge about local markets and work with the voluntary and community sector to identify needs and economic opportunities.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Enable local businesses owned by individuals with protected characteristics to join supply chains through training, simplified and accessible forms, and encourage collective business efforts.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Advertise the diversity of available roles in the organisation through job fairs, community events, ambassador schemes and collaboration with schools and higher education institutions.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Organise flexible, in-person recruitment events in community venues where recruiters can directly meet with candidates.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Remove paperwork barriers in recruitment processes and/ or provide support to candidates to minimise workload and accelerate job start.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Offer work placements to people with protected characteristics and lived experience of disadvantage with practical and psychological support during at least theinitial stages.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Increase participation of people with lived experience of socioeconomic disadvantage in high leadership positions.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Enable all members of staff to undertake leadership role through training and open communication channels across the organization.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Apply lessons learned during the pandemic about undertaking leadership in the community to address social determinants of health and engage with communities.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Contribute to joint local leadership schemes that enable participants to learn from each other and adopt a system approach in dealing with local challenges.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Work with local communities to identify opportunities for the use of organisational spaces by community organisations and businesses.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies and general practices

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

|

Align capital investment decisions with sustainability and anchor activity goals.

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts

|

⊕ ⊕ Low |

*GRADE certainty communicates the strength of evidence for each recommendation.

Recommendations which are supported by large trials will be graded highest whereas those arising from small studies or transferable evidence will be graded lower. The grading should not be interpreted as priority for policy implementation – i.e. somerecommendations may have a low GRADE rating but likely to make a substantial population impact.

How this brief was produced

What is the Living Evidence Map on what works to achieve equitable lipid management in primary care?

Using AI-powered software called EPPI-Reviewer, the Health Equity Evidence Centre has developed a Living Evidence Map of what works to address health inequalities in primary care. The software identifies research articles that examine interventions to address inequalities. The evidence map contains systematic reviews, umbrella reviews. More information can be found on the Health Equity Evidence Centre website.

Funding

This Evidence Brief has been commissioned by NHS England to support their statutory responsibilities to deliver equitable health care. Policy interventions beyond health care services were not in scope. The content of this brief was produced independently by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NHS England.

Suggested citation

Gkiouleka A, Blythe J, Gajria C, Harasgama S, Holdroyd I, Dehn Lunn A, Painter H, Pearce H, Vodden A, Ford J. Evidence brief: What works: How health care organisations can reduce inequalities in social determinants of health in their role as anchor institutions. Health Equity Evidence Centre; 2024

References

- Koh Howard K, Bantham Amy, Geller Alan C, Rukavina Mark A, Emmons Karen M, Yatsko Pamela, et al. Anchor Institutions: Best Practices to Address Social Needs and Social Determinants of Health. American journal of public health. 2020;110(3):309–16.

- Reed S, Göpfert A, Wood S, Allwood D, Warburton W. Building healthier communities: the role of the NHS as an anchor institution. The Health Foundation. 2019

- Vize R. Hospitals as anchor institutions: how the NHS can act beyond healthcare to support communities. Bmj. 2018;361.

- NHS England » Anchors and social value [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 30].

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/our-approach-to-reducing-healthcare-inequalities/anchors-and-social-value/ - Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health. Oup Oxford; 2005.

- NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2024 Sep 4].

Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf - NHS England Digital [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 10]. NHS Workforce Statistics – November 2022 (Including selected provisional statistics for December 2022).

Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/november-2022 - NHS England » Our funding [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 10].

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publications/business-plan/our-2022-23-business-plan/our-funding/ - NHS England Digital [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 10]. Estates Returns Information Collection, Summary page and dataset for ERIC 2021/22.

Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/estates-returns-information-collection/england-2021-22 - Gruen RL, Pearson SD, Brennan TA. Physician-citizens— public roles and professional obligations. Jama. 2004;291(1):94–8.

- Exworthy M, Morcillo V. Primary care doctors’ understandings of and strategies to tackle health inequalities: a qualitative study. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2019;20:e20

- Anchors in a storm – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 18].

Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/anchors-in-a-storm - Anchor institutions: innovating through partnership in challenging times | NHS Confederation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 18].

Available from: https://www.nhsconfed.org/articles/anchor-institutions-innovating-through-partnership-challenging-times - The King’s Fund [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 10]. Anchor Institutions And How They Can Affect People’s Health

Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/anchor-institutions-and-peoples-health - Lewis S. Caring Times. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 10]. Wes Streeting explains how NHS and care could make UK billions.

Available from: https://caring-times.co.uk/wes-streeting-explains-how-nhs-and-care-could-make-uk-billions/ - Allen Matilda, Marmot Michael, Allwood Dominique. Taking one step further: five equity principles for hospitals to increase their value as anchor institutions. Future healthcare journal. 2022;9(3):216–21.

- Gkiouleka Anna, Munford Luke, Khavandi Sam, Watkinson Ruth, Ford John. How can healthcare organisations improve the social determinants of health for their local communities? Findings from realist-informed case studies among secondary healthcare organisations in England. BMJ open. 2024;14(7):e085398.

- Franz Berkeley, Skinner Daniel, Kerr Anna M, Penfold Robert, Kelleher Kelly. Hospital-Community Partnerships: Facilitating Communication for Population Health on Columbus’ South Side. Health communication. 2018;33(12):1462–74.

- Nandyal Samantha, Strawhun David, Stephen Hannah, Banks Ashley, Skinner Daniel. Building trust in American hospital-community development projects: a scoping review. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives. 2021;11(4):439–45.

- Dave Gaurav, Wolfe Mary K, Corbie-Smith Giselle. Role of hospitals in addressing social determinants of health: A groundwater approach. Preventive medicine reports. 2021;21:101315.

- Jones Vanya, Johnson Audrey, Bryan Jacqueline, Mc- Keever Marissa, Hafey Elizabeth, Wilson Alicia. Just Us Dialogues: Harnessing the Transformational Power of Discourse to Prevent Violence. Health security. 2021;19(S1):S57–61.

- Galiatsatos P, Monson K, Oluyinka M, Negro D, Hughes N, Maydan D, et al. Community Calls: Lessons and Insights Gained from a Medical–Religious Community Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Relig Health. 2020 Oct 1;59(5):2256–62.

- Mughal R, Thomson LJ, Daykin N, Chatterjee HJ. Rapid evidence review of community engagement and resources in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: how can community assets redress health inequities? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(7):4086.

- Calthorpe Lucia, Isaacs Eric, Chang Anna. Safety-Net Hospitals as Community Anchors in COVID-19. Journal of patient experience. 2020;7(4):436–8.

- Reddy Michael S. Anchor institutions are important not just during trying times. Journal of dental education. 2021;85(5):605

- Aagaard Eva M, Earnest Mark. Educational leadership in the time of a pandemic: Lessons from two institutions. FASEB bioAdvances. 2021;3(3):182–8.

- Cene Crystal W, Towns Randi J. Sidebar: Time, Talent, and Treasure: Health Systems and the Anchor Mission Strategy for Advancing Health Equity. North Carolina medical journal. 2022;83(1):13–5.

- Boulding Harriet, Hinrichs-Krapels Saba. Factors influencing procurement behaviour and decision-making: an exploratory qualitative study in a UK healthcare provider. BMC health services research. 2021;21(1):1087.

- Health Anchors Learning Network [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 12]. Diversifying NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Supply Chain.

Available from: https://haln.org.uk/case-studies/diversifying-supply-chain - Weston Marla J, Pham Bich Ha, Zuckerman David. Building Community Well-being by Leveraging the Economic Impact of Health Systems. Nursing administration quarterly. 2020;44(3):215–20

- Business in the community. Factsheet: employers that have banned the box [Internet].

Available from: https://www.bitc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/bitc-employers-that-have-banned-the-box-march24v2.pdf - Business in the community. Ban the Box Campaign Report – 1 million jobs later [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 19].

Available from: https://www.bitc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/bitc-report-ban-the-box-one-million-jobs-later-feb21.pdf#page=7.53 - Health Anchors Learning Network [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 13]. The Kickstart Scheme

Available from: https://haln.org.uk/case-studies/the-kickstart-team - Rose TC, Daras K, Manley J, McKeown M, Halliday E, Goodwin TL, et al. The mental health and wellbeing impact of a Community Wealth Building programme in England: a difference-in-differences study. The Lancet Public Health. 2023 Jun 1;8(6):e403–10

- Learning to Lead Together in Newcastle | NHS Confederation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 13].

Available from: https://www.nhsconfed.org/case-studies/learning-lead-together-newcastle - Kickstart Scheme | NHSBSA [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 18].

Available from: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/kickstart-scheme - Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Public Land for Housing Programme 2015 –2020. Programme Handbook for Departments and Arm’s Length Bodies. August 2018 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Sep 20].

Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/863615/Public_Land_for_Housing_programme_2015_to_2020_handbook_Feb_2020.pdf - NHS Property and Estates

- Drabo Emmanuel Fulgence, Eckel Grace, Ross Samuel L, Brozic Michael, Carlton Chanie G, Warren Tatiana Y, et al. A Social-Return-On-Investment Analysis Of Bon Secours Hospital’s “Housing For Health” Affordable Housing Program. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2021;40(3):513–20.

- Bon Secours Baltimore Health System. Community health needs assessment [Internet]. Baltimore; 2016.

- Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England.

- Greener NHS » National ambition [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 20].

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/national-ambition/ - Hardi J. Sustainability strategies for healthcare estates: Lessons from University College London hospitals. 2012.