What works: Designing health care inclusively for people with low incomes

The NHS Constitution states that access to NHS services is based on clinical need, not an individual’s ability to pay. Most NHS services are free of charge. There is a large evidence base describing the problems that people with low incomes face accessing healthcare; much of the international literature relates to insurance premiums. However, there is little research describing how to ensure people on low incomes are not inadvertently excluded from healthcare services.

What works – designing health care inclusively for people with low incomes[PDF 249kb]

Download documentSummary

The NHS Constitution states that access to NHS services is based on clinical need, not an individual’s ability to pay. Most NHS services are free of charge. For those services which require copayment, such as dentistry, optometry, prescriptions, and wigs and fabric support, there is provision (to some extent) for those who cannot afford to pay through the NHS Low Income Scheme and allowances for those who receive certain benefits, such as Universal Credit and Income Support. The NHS Low Income Scheme also supports transport costs. About 250,000 people are supported each year through the NHS Low Income Scheme, but we do not know how many people the scheme misses. Accessing financial support has previously faced criticism for its complexity, leading to some individuals missing out on the support they are entitled to.

There are other out-of-pocket costs which may inadvertently exclude people on low incomes. These include transport, parking and childcare costs, income lost due to time off work, subsistence costs for carers during unplanned hospital attendances and admissions, and costs of following clinical advice, such as dietary and lifestyle changes. In North America, many healthcare organisations ask people about social difficulties, record them in the electronic health record, and offer support. The UK does not routinely collect or use this type of information.

There is a large evidence base describing the problems that people with low incomes face accessing healthcare; much of the international literature relates to insurance premiums. However, there is little research describing how to ensure people on low incomes are not inadvertently excluded from healthcare services. Improving flexibility in the timing and mode of consultations, whether face-to-face or remote, is likely to support people with low incomes. People on low incomes can ill-afford time off work to attend in-person appointments in working hours. Community outreach activities, such as appropriately targeted drop-in events and mobile units, would help opportunistic engagement in preventative services. Additionally, screening for social needs and offering support would address these needs, in addition to co-locating welfare advisors. Food prescriptions may help people on low incomes who require costly diets. Some NHS organisations are already taking action to ensure people on low incomes are not excluded, such as Poverty Proofing in the North East of England.

Current challenges

There are decades of evidence linking low income and poor health [1]. People on low incomes have more risk factors, such as smoking, poor diet, and limited physical activity, and more health problems, culminating in shorter lives [2]. There are currently 14.3 million people living in relative poverty in the UK after housing costs (21% of the population) [3]. The causal pathway is multifactorial and likely to build up over the life course, including the impact of chronic stress, poor quality housing, lack of access to green spaces, pollution, and access to cheaper ultra-processed food [4]. Inclusion health groups, such as people who are homeless and those seeking asylum, are particularly vulnerable to the compounding effects of poverty.

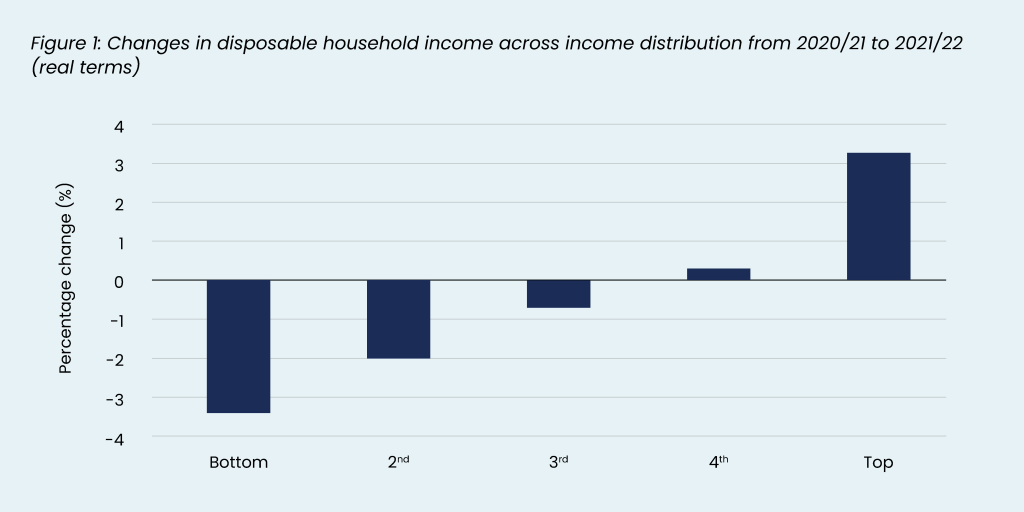

The mean disposable income has only increased slightly in the past 14 years. In 2007/08 it was £38,670 in real terms and in 2021/22, £39,328 [5]. Income inequalities remain high – in 2022/23, for a couple without children, the lowest 10% had a disposable income of £300 per week before housing costs compared to £1200 for those in the highest 10% [6]. There are signs that inequalities in disposable income have been worsening. Between 2020/21 and 2021/22, people in the top 20% saw their disposable income increase by 3.3%, but those in the lowest 20% saw it reduce by 3.4% [5].

Addressing the root causes of these issues lies outside the remit of the health care system. However, people who are on a low income can have problems accessing and using NHS care – while NHS care is free at the point of use, there are often many unexpected out-of-pocket expenses which patients must cover. This may include travel, lost income, childcare, and subsistence during unplanned attendances. These barriers may mean that some people delay seeking care or miss appointments or treatment.

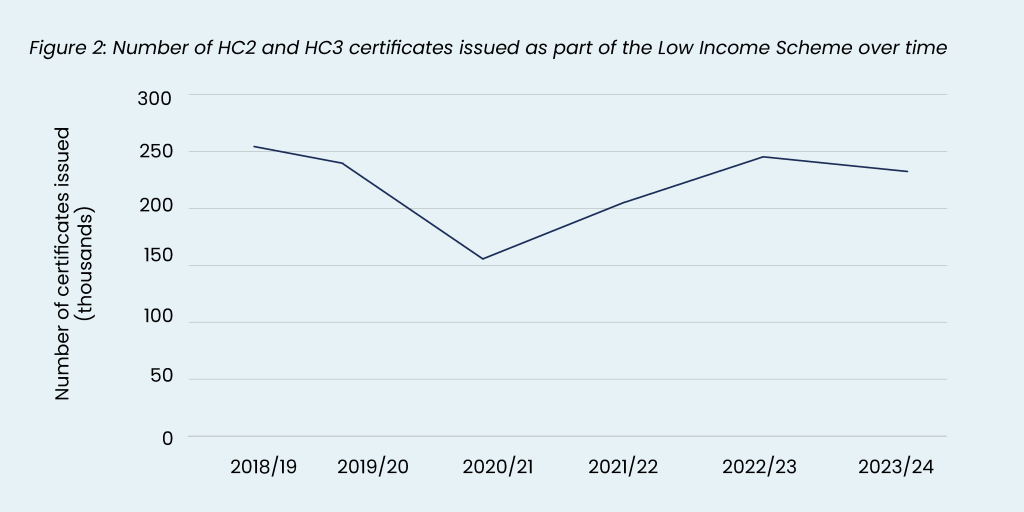

The NHS has a Low Income Scheme which covers 1) prescription costs, 2) dental costs, 3) eye care costs, 4) healthcare travel costs, and 5) wigs and fabric supports [7]. It is available for anyone with savings, investment, or property (excluding an individual’s home) of less than £16k, or £23,250 for those in a care home, and whose income is less than their weekly requirements (according to their Low Income Scheme assessment). There were 232,550 certificates issued as part of the Low Income Scheme in 2023/24 in England, which has risen since the pandemic (from 155,555 in 2020/21) but has not returned to pre-pandemic levels [8]. A qualitative study in the North East of England published in 2024, found that people on low incomes were often not aware of the financial support available and often found out ‘by chance’ [9]. Furthermore, people on certain benefits, such as Universal Credit and Income Support, are also eligible for financial support. Social welfare legal advice helps in some areas with supporting patients to access the financial support and some pharmacies automatically check eligibility for free prescriptions, but services are patchy.

Since people on low incomes have the poorest health, it is imperative that they are not inadvertently excluded from NHS services because of unexpected out-of-pocket costs. Here we review the evidence of what works to mitigate the barriers faced by people on low incomes when using health care services, while acknowledging that the root causes lie outside the responsibility of the health care services.

Summary of evidence

We identified studies through 1) Living Evidence Maps developed by the Health Equity Evidence Centre [10], 2) a search of an electronic database (MEDLINE) examining what works to address inequalities through healthcare, and 3) snowballing by citation tracking and a machine learning tool (Litmaps). In total, we prioritised 21 research studies which provided the highest quality evidence on what works to ensure NHS services do not exclude people on low incomes. These studies were either recent high-quality systematic reviews on a topic or particularly relevant to the UK context.

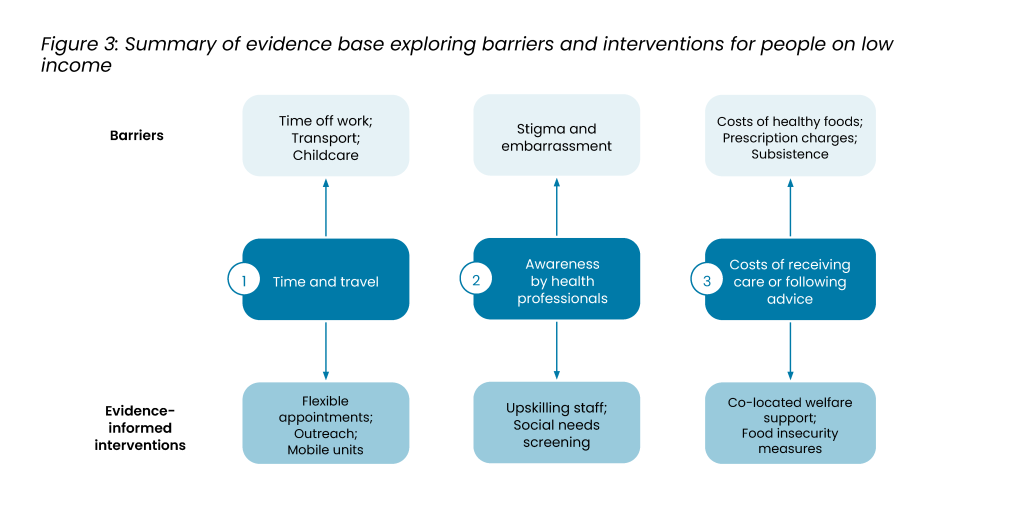

The majority of the international literature focuses on the cost of insurance in countries without universal healthcare coverage. There are many UK studies which describe the experiences of people facing poverty or access barriers, such as transport, but far fewer examining how to ensure healthcare does not exclude people on low incomes. The evidence is divided into three main categories – 1) costs associated with time and travel, 2) awareness of financial difficulties by health professionals, and 3) the costs of receiving care or following advice.

1. Time and travel costs

The problems for people on low incomes accessing health care have been well-described in the literature [11][12][13][14][15]. In a qualitative study of 24 parents and 8 Voluntary Community Social Enterprise sector staff based in the north-east of England undertaken in 2021/22, Bidmead and colleagues found a range of problems low-income parents face [9]. The authors found that people on low incomes faced potential barriers in terms of accessing the internet for digital appointments, the cost of remaining on hold while waiting to speak to a GP receptionist, being able to take time off work to attend appointments, and the cost of childcare to attend appointments. The authors found that travel costs to their GP surgery were often minimal, but attending hospital appointments was difficult because it often required multiple bus journeys or excessive parking fees. One parent reported spending up to £50 on travel to a hospital appointment, which meant that they would sometimes cancel the appointment.

In a UK survey of 574 women attending antenatal screening published in 2016, 36% lost pay because they took unpaid absence or would make the time up, and 71% of women came with someone who also had taken time off work [16]. The authors estimated that the time cost to attend an appointment was £22 per visit. Ten per cent of women said they were losing income through attending the clinic, ranging from £3 to £250.

Ford and colleagues (2016) reviewed 163 studies examining the problems older people in rural areas on low incomes face accessing primary care in a realist review [11]. They found that an individual’s financial resources impact their decision to seek help from their GP either because they were concerned about the financial implications of receiving a diagnosis or the cost of transport. Transport was especially important for older people who did not have access to a car within their household and for whom services were not nearby. While most people were able to find transport eventually, they often made a decision balancing the substantial effort and cost of arranging transport over perceived benefit.

Younger people also report cost barriers. A UK survey of 203 young people aged 18-25 were asked about barriers in accessing mental health services; 26% of people reported cost as a major barrier [13].

Gkiouleka and colleagues undertook a realist review of interventions to address inequalities in primary care [17]. Based on the 159 studies that were included, the authors found that flexibility was one of five key guiding principles to reduce inequalities – i.e., organisations should make allowances according to different patients’ needs. This would include being flexible about the model of appointment (e.g., remote or face-to-face) and timing (e.g., options outside working hours). This is supported by Tierney and colleagues’ review (2023) of telemedicine for low-income patients [18]. Based on 45 studies from the US, the authors found that for some patients, telemedicine was more affordable and increased access for those with prohibitive travel or childcare costs. Telemedicine requires digital health literacy which may be a barriers to some disadvantaged groups (see complementary evidence brief on Health and Digital Literacy).

Outreach interventions with opportunistic services may overcome the costs people on low incomes face to attend healthcare. Roberts and de Souza (2016) reviewed outreach venues to increase the uptake of NHS health checks in people living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, men, and South Asians in Buckinghamshire [19]. Based on 3,849 health checks undertaken, the authors found that supermarkets and libraries had the highest uptake, but mosques and bus stations had the highest uptake for disadvantaged communities. A greater number of men also took part at manufacturing workplaces and football matches.

Mobile drop-in stop smoking services have also been found to be effective in increasing the uptake of disadvantaged groups. Venn and colleagues (2014) evaluated drop-in stop smoking services in various public venues across Nottingham and compared them with the standard services at a fixed location [20]. Based on 811 people using the mobile service, compared to 1,856 using the standard service, the authors found that people who used the mobile service were statistically significantly more likely to be from routine or manual occupational groups (33.3% vs 27.2%), first-time users of the service (67.8% vs 59.3%), and live in low-income areas with high social housing (27% vs 26%). The cost of the mobile service per smoker setting a quit date was only slightly higher than the fixed location (£224 vs £202).

2. Awareness by health professionals

A considerable volume of a GP’s time is taken with social issues. Approximately 1 in 5 GP consultations are due to a social issue costing £400 million per year [21]. Most of these consultations are due to relationships (92%), housing (77%), or work/ unemployment (76%). Bidmead and colleagues in the qualitative study in the north-east of England found that there was a lack of a systemic approach to supporting patients living in poverty and help usually relied on individual health professionals [9]. A survey of 526 people with mental health problems by Mind found that people feel shame and stigma if they do not have enough money, especially if there are visible issues, such as being on benefits, using food banks, getting into debt, or having to ask for help from friends or family [22].

Healthcare organisations in North America have been ‘screening’ for social needs for several years. Social needs screening involves asking patients about social issues in order to identify those who may benefit from help and refer them to onward support. In the UK, healthcare organisations do not routinely screen for social needs, although there have been various calls for it [23][24][25]. Yan and colleagues (2022) undertook a review of social needs screening in clinical settings [26]. Half of the 28 included studies were RCTs and 11 reported on health outcomes. Interventions ranged from staff identifying social risk and distributing a leaflet of community resources or signposting to support from a patient navigator or social worker. The authors found that positive short-term impacts included increased smoking cessation rates, improved child health (caregiver self-report), better blood pressure control, decreased intimate partner violence, lower cholesterol, increased fruit and vegetable consumption, and improved self-rated health. The authors also found evidence for improved adherence to treatment, immunisation rates, reduced A&E attendance and hospital readmissions. Other reviews have found that social needs screening is successful in identifying people with financial problems [27][28][29]. De Marchis and colleagues (2023) reviewed implementation factors of social needs screening and found that time was the most cited barrier, but that standardisation of tools and workflow helped [30]. The authors also found that community health workers and technology helped patients to share information and facilitated screening in a resource-limited setting.

In June 2023, the first financially incentivised social needs screening programme was implemented in North East London (NEL) Integrated Care Board (ICB) based on research showing that 38% of people in Hackney found it difficult to ‘make ends meet at the end of the month’ [31]. The Data Accreditation and Improvement Incentive Scheme (DAiiS) incentivises GP practices to collect data on wider determinants of health [32]. Practices are paid to ask four questions exploring literacy, financial instability, housing instability, and social isolation, with codes embedded in the electronic health record (EHR). Questions are targeted to new registrations and existing patients in the most deprived IMD quintile. Those answering yes to any question are offered referral to social prescribing. Evaluation is ongoing.

Moscrop and colleagues reviewed the reasons for and against social needs screening in 2019 [24]. Most academic articles supported social needs screening to improve outcomes, support health care service monitoring and provision and population health approach. However, 8 of 138 articles raised concerns about potential harms, professional boundaries and onward use of data.

3. Costs of receiving care or following advice

Patients on low incomes can also find services which require copayment, such as prescription charges, difficult. Unplanned hospital attendance or the advice of healthcare staff may also incur unexpected costs.

In England, there is a prescription charge currently of £9.90 for people aged 18-60 years. There are a number of exemptions, including those who receive means-tested benefits, certain conditions, pregnant women, and those who have recently had a baby. Asthma, for example, is not included in the list of long term conditions which are eligible for free prescriptions. People on low incomes can apply for free prescriptions under the NHS Low Income Scheme. Both Scotland and Wales have abolished the prescription charge. An evaluation in 2018 in Scotland found mixed results and could not draw conclusions on the impact on inequalities [33]. An evaluation in Wales in 2011 found a statistically significant increase in the number of prescriptions and a reduction in the number of medications bought; however, there was little or no impact on those on the lowest incomes [34].

Case study: Poverty proofing in the North East

Children North East is a charity in the North East of England that delivers services, support, and initiatives for children, young people, and families. They have developed a Poverty Proofing stream of work and won the ‘Most Impactful Project Addressing Health Inequalities’ at the HSJ Partnership Awards 2022. They work with healthcare organisations to think about how to ensure healthcare services do not exclude people in poverty.

In 2021, they were commissioned by the North East and North Cumbria Child Health and Wellbeing Network to explore the financial barriers that exist for children and young people accessing healthcare [45]. Based on surveys and group consultations in the North East, they found the following hidden costs that may exclude people on low incomes from healthcare:

- Transport was the most frequently reported expense.

- Appointment times and availability were a barrier, especially in relation to work and childcare.

- Remote consultations reduced time and travel barriers for some, but people who were not proficient in English found them difficult.

- Hospitals were the most challenging location, including parking costs and food costs for parents while accompanying children, especially if unplanned.

- Those with long-term conditions and disabilities requiring frequent healthcare described the most financial impact.

Based on this work, the authors recommended:

- Working with people on low incomes to understand the hidden costs in different health care settings.

- Collating best practice, developing support guidelines and sharing across health care settings.

- Raising awareness amongst staff of the causes and consequences of living in poverty and services available.

Two reviews examined the colocation of welfare advisors in health care settings. Reece and colleagues (2022) reviewed 14 studies of co-located welfare services in the UK, mostly in general practice through Citizens Advice and reaching people on low incomes and those not in work [35]. The authors found that all studies found an improvement in financial security with an average financial gain of £776 to £3656 and an improvement in the financial literacy of both patients and staff. There was also an 7% average reduction in GP attendance after co-location of a welfare advisor. Young and colleagues (2022) included 15 articles which evaluated free to access advice services on social welfare issues [36]. The authors found improvements in mental heath and wellbeing services and co-locating services supports collaboration between organisations to tackle the social determinants of health.

Bidmead and colleagues in the qualitative study also reported the cost of food and drinks during hospital attendance as significant challenges [9]. They reported that food was not provided for parents staying with a child, even if the mother is breastfeeding. It was particularly costly for unplanned admissions when parents and carers could not plan ahead. The authors also found costs associated with discharge from ED or an admission, especially when this was with children or when public transport was not operating.

There can be ongoing financial consequences of illness. Ngan and colleagues (2022) looked at the financial implications of surviving cancer in the UK [37]. Based on 29 included studies, the authors found that many survivors and/or carers faced severe financial problems, such as debt and difficulty paying a mortgage, leading to mental health problems and being forced to return to work prematurely.

Several studies reported on the cost of eating a healthy diet, especially when advised by their doctor because of a health problem. The Food Foundation estimate that most deprived fifth of the population would need to spend 50% of their disposable income on food to meet the cost of the Government recommended healthy diet [38]. This compares to just 11% for the least deprived fifth. Woodward and colleagues (2024) found 12 studies that reported that people with diabetes on low incomes found it difficult to afford healthy food [39]. For example, one participant said, ‘I don’t have a lot of money … so I’ll buy junk food, instead of real food, because the junk food is cheaper.’ Marteau and colleagues noted that increasing household income in poorest households increases spending on fruit and vegetables and reduces spending on tobacco and alcohol [40].

Several Food is Medicine initiatives across the US support patients to eat healthily, addressing food insecurity and nutrition simultaneously. Mozaffarian and colleagues (2024) in their summary of the programme highlight treatment support patients can receive from food prescriptions, medically tailored groceries, and medically tailored meals [41]. Little and colleagues (2022) reviewed 23 studies examining food prescription programmes [42]. The authors found food prescriptions improved fruit and vegetable consumption and reduced food insecurity, but there remained barriers of stigma, transport, and nutritional literacy. Hager and colleagues (2023) evaluated 22 food prescription sites across 12 US states, including 3,881 patients from low-income areas [43]. The researchers found, at 6 months, a reduction in food insecurity, improved self-reported health, reduced HbA1c, blood pressure, and obesity. However the transferability of this to the UK context is unknown with the Institute for Health Equity recommending cash transfers rather than food aid [44].

Case study: Fruit and veg prescriptions in Bromley by Bow and Lambeth

In 2022, the Alexandra Rose Charity launched a pilot in collaboration with GPs in Bromley by Bow and Lambeth to provide people with food insecurity with a food voucher for fruit and vegetables [46]. Participants of the scheme are given up to £8 per week and an additional £2 per household member to spend in several fruit and veg shops, mostly in local markets to support the local economy. An evaluation, based on 91 users, found that 91% of recipients had multiple long term conditions, 85% were unemployed due to health reasons and 82% were food insecure. On average, users were eating 3.2 more portions of fruit and veg per day and there was a 40% reduction in GP visits over 8 months and 60% of people reported using less medication to control diabetes, heartburn and acid reflux.

Further considerations

The lack of UK studies examining how to ensure the NHS does not exclude people on low incomes reflects broad agreement in the literature that the policy mechanisms should focus on increasing the income of people on low incomes, rather than make public services more accessible to people on low incomes. Supporting people on low income requires adequate time and resources, especially in general practice. However there is good evidence that general practices in more deprived areas have fewer GPs and less funding than more affluent areas (see our analysis of general practice inequalities here).

What works: key recommendations

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) [37] framework has been adopted to grade the quality of the evidence and support recommendations.

Recommendations which are supported by large trials will be graded highest whereas those arising from small studies or transferable evidence will be graded lower. The grading should not be interpreted as priority for policy implementation – i.e. some recommendations may have a low GRADE rating but likely to make a substantial population impact.

| Recommendation | Target audience | GRADE certainty |

| Raise awareness amongst staff of the impact of poverty, how to raise the issue without stigmatising patients and the support that is available. | General practices, PCNs, ICBs, NHS England | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

| Co-locate welfare advisors in health care settings, especially general practice, to increase awareness of financial support schemes, improve financial literacy of patients and staff and raise the income of those on low incomes. | NHS England, General practices, NHS Trusts, ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

| Raise awareness of financial support available for people on low incomes among staff and consider free parking for people on low incomes. | NHS Trusts | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

| Ensure appointment times and mode (face-to-face or remote) are flexible to allow people on low incomes to reduce the cost of travel, childcare or lost income, with organisations provided with resources to provide these services. | NHS England, General practices, NHS Trusts, ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

| Consider community outreach activities in low income areas, such as drop-in events or mobile units, for preventative services which avoid travel and facilitate opportunistic participation. | ICBs, Local Authorities | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

| Ensure food and drink are freely offered to patients and carers during hospital visits. | NHS Trusts | ⊕ ⊕

Low |

| Consider social needs screening in general practice to identify people in financial difficulty to offer support and tailor services. | General practices, PCNs, ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

| Consider the provision of financial support, such as food vouchers, for people on low incomes who face food insecurity or require certain diets to control their health conditions (e.g. diet controlled diabetes mellitus). | ICBs, NHS England | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕

Moderate |

How this brief was produced

What is the Living Evidence Map on what works to achieve equitable lipid management in primary care?

Using AI-powered software called EPPI-Reviewer, the Health Equity Evidence Centre has developed a Living Evidence Map of what works to address health inequalities in primary care. The software identifies research articles that examine interventions to address inequalities. The evidence map contains systematic reviews, umbrella reviews. More information can be found on the Health Equity Evidence Centre website.

Funding

This Evidence Brief has been commissioned by NHS England to support their statutory responsibilities to deliver equitable health care. Policy interventions beyond health care services were not in scope. DL is funded by NIHR ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of NHS England or NIHR.

Useful links

Suggested citation

Ford J, Engamba S, Gkiouleka A, Lamb D, Loftus L, Torabi P. Evidence brief: What works – Designing health care inclusively for people with low incomes. Health Equity Evidence Centre; 2024

References

- Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ. 2020 Feb 25;368:m693.

- Health Foundation. Quantifying health inequalities in England. 2022

Available from: https://health.org.uk/%20news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/quantifying-%20health-inequalities - Francis-Devine B. Poverty in the UK: statistics. 2024 Aug 28 [cited 2024 Aug 28]

Available from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn07096/ - Evidence hub: What drives health inequalities? – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/evidence-hub - Office for National Statistics. Average household income, UK [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/householddisposableincomeandinequality/financialyearending2022 - Francis-Devine B. Income inequality in the UK [Internet]. House of Commons Library; 2024 Apr [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7484/CBP-7484.pdf - NHS. Low Income Scheme (LIS) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/nhs-services/help-with-health-costs/nhs-low-income-scheme-lis/ - NHSBSA. Help with Health Costs – England 2023/24 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/statistical-collections/help-health-costs/help-health-costs-england-202324 - Bidmead E, Hayes L, Mazzoli-Smith L, Wildman J, Rankin J, Leggott E, et al. Poverty proofing healthcare: A qualitative study of barriers to accessing healthcare for low-income families with children in northern England. PLOS ONE. 2024 Apr 26;19(4):e0292983.

- Health Equity Evidence Centre [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Evidence maps.

Available from: https://www.heec.co.uk/component-library/evidence-maps/ - Ford JA, Wong G, Jones AP, Steel N. Access to primary care for socioeconomically disadvantaged older people in rural areas: a realist review. BMJ Open. 2016 May 1;6(5):e010652.

- Kang C, Tomkow L, Farrington R. Access to primary health care for asylum seekers and refugees: a qualitative study of service user experiences in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Aug;69(685):e537–45.

- Salaheddin K, Mason B. Identifying barriers to mental health help-seeking among young adults in the UK: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2016 Oct 1;66(651):e686–92.

- Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, Waite P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 Feb 1;30(2):183–211.

- Dawkins B, Renwick C, Ensor T, Shinkins B, Jayne D, Meads D. What factors affect patients’ ability to access healthcare? An overview of systematic reviews. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2021;26(10):1177–88.

- Verhoef TI, Daley R, Vallejo-Torres L, Chitty LS, Morris S. Time and travel costs incurred by women attending antenatal tests: A costing study. Midwifery. 2016 Sep;40:148– 52.

- Gkiouleka Anna, Wong Geoff, Sowden Sarah, Bambra Clare, Siersbaek Rikke, Manji Sukaina, et al. Reducing health inequalities through general practice. The Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(6):e463–72.

- Tierney AA, Mosqueda M, Cesena G, Frehn JL, Payán DD, Rodriguez HP. Telemedicine Implementation for Safety Net Populations: A Systematic Review. Telemedicine Journal and E-health. 2023;

- Roberts DJ, de Souza VC. A venue-based analysis of the reach of a targeted outreach service to deliver opportunistic community NHS Health Checks to ‘hard-toreach’ groups. Public Health. 2016;

- Venn A, Dickinson A, Murray R, Jones L, Li J, Parrott S, et al. Effectiveness of a mobile, drop-in stop smoking service in reaching and supporting disadvantaged UK smokers to quit. Tob Control. 2016 Jan;25(1):33–8.

- Citizen Advice. A Very General Practice [Internet]. 2015 May [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Public%20services%20publications/CitizensAdvice_AVeryGeneralPractice_May2015.pdf - MIND. Mind: Fighting for the MH of people living in poverty [Internet]. 2021 Aug [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/media/12428/final_poverty-scoping-research-report.pdf - Gopal DP, Beardon S, Caraher M, Woodhead C, Taylor SJ. Should we screen for poverty in primary care? Br J Gen Pract. 2021 Oct 1;71(711):468–9.

- Moscrop A, Ziebland S, Roberts N, Papanikitas A. A systematic review of reasons for and against asking patients about their socioeconomic contexts. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2019 Jul 23;18(1):112.

- Moscrop A, Ziebland S, Bloch G, Iraola JR. If social determinants of health are so important, shouldn’t we ask patients about them? BMJ. 2020 Nov 24;371:m4150.

- Yan AF, Chen Z, Wang Y, Campbell JA, Xue QL, Williams MY, et al. Effectiveness of Social Needs Screening and Interventions in Clinical Settings on Utilization, Cost, and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):454–75.

- Kim RG, Ballantyne A, Conroy MB, Price JC, Inadomi JM. Screening for social determinants of health among populations at risk for MASLD: a scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024;

- Pourat N, Lu C, Huerta DM, Hair BY, Hoang H, Sripipatana A. A Systematic Literature Review of Health Center Efforts to Address Social Determinants of Health. Med Care Res Rev. 2023 Jun;80(3):255–65.

- Gottlieb LM, Wing H, Adler NE. A Systematic Review of Interventions on Patients’ Social and Economic Needs. Am J Prev Med. 2017 Nov;53(5):719–29.

- De Marchis Emilia H, Aceves Benjamin, Brown Erika, Loomba Vishalli, Molina Melanie F, Gottlieb Laura M. Assessing Implementation of Social Screening Within US Health Care Settings: A Systematic Scoping Review. Journal Of The American Board Of Family Medicine. 2023;36(4):626– 49.

- Homer K, Taylor J, Miller A, Pickett K, Wilson L, Robson J. Making ends meet – relating a self-reported indicator of financial hardship to health status. J Public Health (Oxf). 2023 Nov 29;45(4):888–93.

- Data Accreditation and Improvement Incentive Scheme – Clinical Effectiveness Group [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21]

Available from: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/ceg/support-for-gp-practices/resources/gp-contract-guidance/daaiis/ - Williams AJ, Henley W, Frank J. Impact of abolishing prescription fees in Scotland on hospital admissions and prescribed medicines: an interrupted time series evaluation. BMJ Open. 2018 Dec 18;8(12):e021318.

- Groves S, Cohen D, Alam MF, Dunstan FDJ, Routledge PA, Hughes DA, et al. Abolition of prescription charges in Wales: the impact on medicines use in those who used to pay. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010 Dec;18(6):332–40.

- Reece S, Sheldon TA, Dickerson J, Pickett KE. A review of the effectiveness and experiences of welfare advice services co-located in health settings: A critical narrative systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2022 Mar 1;296:114746.

- Young D, Bates G. Maximising the health impacts of free advice services in the UK: A mixed methods systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022 Sep;30(5):1713– 25.

- Ngan TT, Tien TH, Donnelly M, O’Neill C. Financial toxicity among cancer patients, survivors and their families in the United Kingdom: a scoping review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2023 Aug 4;45(4):e702–13.

- Tobi R, Saha R, Gurung I, English A, Taylor A, Lobstein T, et al. The Broken Plate 2023. The State of the Nation’s Food System. The Food Foundation; 2023.

- Woodward A, Walters K, Davies N, Nimmons D, Protheroe J, Chew-Graham CA, et al. Barriers and facilitators of self-management of diabetes amongst people experiencing socioeconomic deprivation: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Health Expectations. 2024

- Marteau TM, Rutter H, Marmot M. Changing behaviour: an essential component of tackling health inequalities. BMJ. 2021 Feb 10;372:n332.

- Mozaffarian D, Aspry K, Garfield K, Kris-Etherton P, Seligman H, Velarde GP, et al. ‘Food Is Medicine’ Strategies for Nutrition Security and Cardiometabolic Health Equity: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2024.

- Little M, Rosa E, Heasley C, Asif A, Dodd W, Richter A. Promoting Healthy Food Access and Nutrition in Primary Care: A Systematic Scoping Review of Food Prescription Programs. Am J Health Promot. 2022 Mar;36(3):518–36.

- Hager K, Du M, Li Z, Mozaffarian D, Chui K, Shi P, et al. Impact of Produce Prescriptions on Diet, Food Security, and Cardiometabolic Health Outcomes: A Multisite Evaluation of 9 Produce Prescription Programs in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2023 Sep;16(9):e009520.

- Institute of Health Equity [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 28]. The Rising Cost of Living: A Review of Interventions to Reduce Impacts on Health Inequalities in London

Available from: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/evidence-review-cost-of-living-and-health-inequalities-in-london - North East and North Cumbria, Child Health and Wellbeing Network. Poverty Proofing Health Settings Report [Internet]. 2021 Feb [cited 2024 Aug 21].

Available from: https://children-ne.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/nenc-chwn-poverty-proofing-health-settings-report.pdf - Alexandra Rose [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 28]. Report: Exploring the power of Fruit & Veg on Prescription

Available from: https://www.alexandrarose.org.uk/report-exploring-the-power-of-fruit-veg-on-prescription/ - Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008 Apr 24;336(7650):924–6