What works: Empowering health care staff to address health inequalities

The NHS employs over 1.7 million people in England. Empowering NHS staff to tackle health inequalities offers significant potential. However, several workforce challenges exist. In this brief, we review the international evidence on what works to empower health care staff to address inequalities.

What works: Empowering health care staff to address health inequalities[PDF 288kb]

Download documentSummary

The NHS employs over 1.7 million people in England. Empowering NHS staff to tackle health inequalities offers significant potential. However, several workforce challenges exist. First, while the NHS has a higher proportion of staff from minority ethnic groups compared to the general population, staff from disadvantaged backgrounds have a worse experience and struggle to secure senior positions. Second, there are over 100,000 vacancies across the NHS, leading to staff burnout and poor staff retention. The current workforce arrangement is compounded by existing workload pressures such as inadequate time or lack of appropriate resources, leading to an inability to address health inequalities.

In this brief, we review the international evidence on what works to empower health care staff to address inequalities. It is important to note that the NHS has already taken positive steps to empower its staff, for example through the Core20PLUS Ambassador programme.

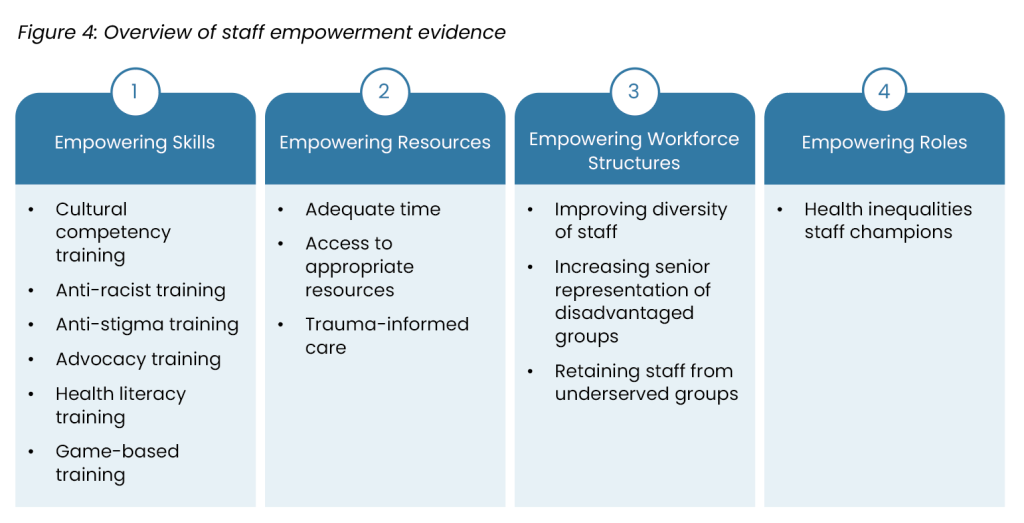

We prioritised 28 articles which were divided into four groups: 1) empowering through skills; 2) empowering through resources; 3) empowering through workforce structure and 4) empowering through staff champions.

We found:

- Good evidence that cultural competency training, anti-racist training, anti-stigma training in mental health and staff health literacy training all improve staff knowledge, skills, and attitudes, however the impact on patient outcomes is unclear.

- Suggestions from small-scale studies that staff need adequate time and culturally relevant resources to act on patient health inequalities.

- Some evidence that empowering staff to use trauma-informed approaches improves care for disadvantaged groups, especially in emergency departments.

- Several initiatives described in the literature to better diversify the workforce and help staff from under-represented groups obtain senior positions, however the studies tend to be small and poorly evaluated. The strongest evidence existed for mentoring programmes.

Current challenges

The NHS is the largest employer in England, employing 1.7 million people or 1 in 17 of all workers [1]. Globally, it is the fifth largest employer [2][3]. An aging population with increasing prevalence of multiple long-term conditions means that the NHS will likely need to employ an estimated 2.3 to 2.4 million people by 2036/37, equivalent to 1 in 11 workers [1]. Mobilising current and future staff, both clinical and non-clinical, to take action to reduce health and care inequalities therefore offers huge potential.

Empowerment: Empowerment is defined as the actions and tools needed to enable health care staff to provide better quality care and advocate for disadvantaged patients.

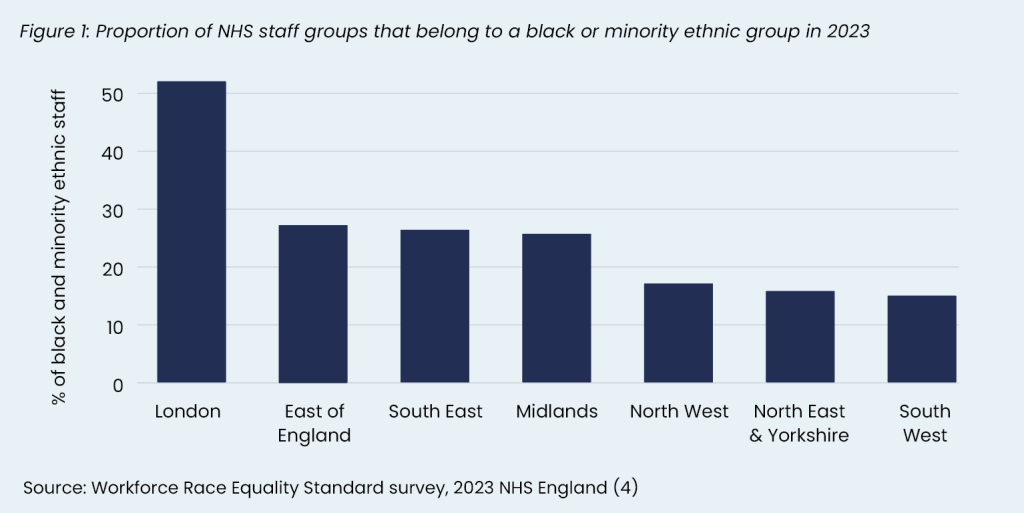

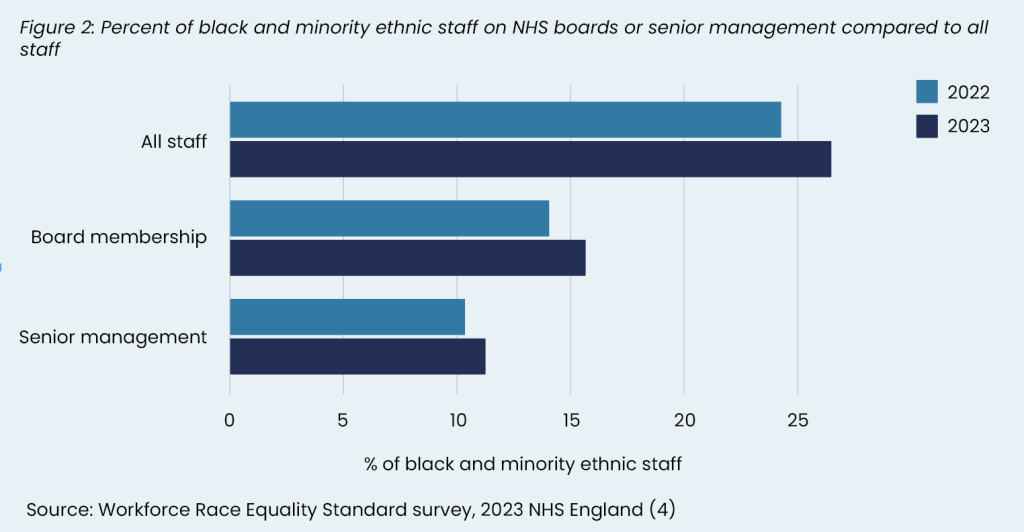

There are several challenges. First, NHS staff from minority ethnic groups report poorer workplace experiences and there is poor diversity in senior staff positions (see Figure 2). About 1 in 4 people working in the NHS are Asian, black or another minority ethnicity, about double that of the general population (25% versus 13% representation) [1]. However, this varies across professional groups, with 39% of nurses being from a minority ethnic group but only 7% of ambulance staff [1]. These staff groups were also more likely to experience discrimination from other staff compared to their white colleagues (16.6% vs 6.7%) [4].

NHS England’s 2023 Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) survey [4] revealed that only 39.3% of black staff believed they had equal opportunities for professional development and progression, lower than those of other ethnic groups. It also revealed that while staff from minority ethnic groups were less likely to be in senior management or board positions, this has improved in recent years. For example, 16% of board members were from black and minority ethnic groups in 2023 compared to 14% in 2022, with an overall 61.7% increase in representation since 2018.

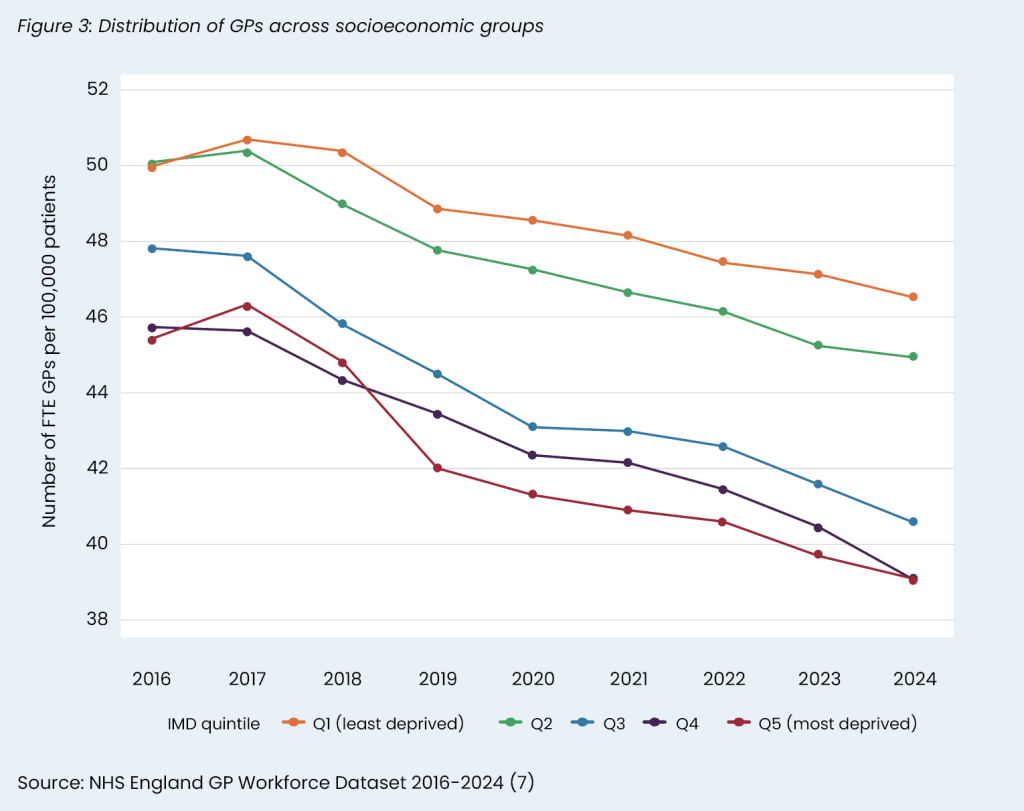

Second, there are many vacancies within the NHS compounded by the workforce not being distributed evenly. Latest data from 2023/24 [5] suggests that 7.6% of NHS positions across secondary and community care remain unfilled – over 110,000 positions. Staff shortages place additional pressure on staff, making it harder to undertake strategic planning activities which are likely to address inequalities, while also contributing to poor staff retention, burnout and low morale. A YouGov survey in June 2024 of over 1200 NHS staff found that 70% of NHS staff were having to take on extra responsibilities because of staff shortages [6]. We do not have data on how secondary and community staff are distributed according to socioeconomic status, but we know that general practices in more affluent areas have more GPs per head of population than more deprived areas, a trend which has been worsening over the last 8 years [7] (see Figure 3). This inequitable distribution of general practice staff makes it harder for practices in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas to improve services.

NHS England has developed a Core20PLUS infrastructure to empower staff to address health inequalities. These include Core20PLUS ambassadors who are clinical or non-clinical staff working within the NHS and wider systems to ensure equitable access, improved experience, and optimal outcomes for all. Staff within the NHS are a considerable asset and empowering them to help address health inequalities has the potential to make a significant difference. Here, we review the evidence of what works to empower health care staff to address health inequalities.

Summary of evidence

We identified 43 studies examining staff empowerment from the HEEC living evidence maps, a MEDLINE search and snowballing. We prioritised 28 studies which were the most high-quality, recent, and applicable studies. Four key themes emerged from the literature: 1) empowering through skills, 2) empowering through resources, 3) empowering through workforce structure, and 4) empowering through staff champions (Figure 4).

Overall, the highest quality evidence suggests that empowering staff with the right skills through training interventions improves knowledge, behaviours, and attitudes towards marginalised patient groups. However, little evidence exists on patient outcomes. There are numerous examples of initiatives which aim to empower staff to address health inequalities, such as trauma-informed care models and developing culturally competent resources, with positive feedback from patients and staff, but lack data on the quantitative impact on outcomes. Equally, there are several initiatives to widen participation, diversify the workforce and help support under-represented groups into senior positions, but they tend to be small-scale studies without robust evaluation.

1. Empowering through skills

Most of the evidence for staff empowerment to address the health needs of disadvantaged groups comes from reviews on training employed staff, most of which focus on cultural competency training. These interventions generally target improving care for three main groups: 1) racial and ethnic minority groups, 2) LGBTQ+ individuals, and 3) people with mental health issues. In this section, we categorised skills-based interventions by training type: 1) cultural competency training for staff, 2) anti-racist training, 3) anti-stigma training, 4) advocacy training, 5) staff training to understand people with low health literacy and 6) health inequalities training through game-based approaches.

Cultural competency training

There is consistent high-quality evidence across multiple published systematic reviews that cultural competency training improves the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of health care staff, but the impact on patient outcomes is less clear [8][9].

Duckhee and colleagues reviewed 11 studies, five of which were randomised controlled trials, and found that nine reported positive outcomes on health professionals’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but only one of the three studies that reported patient outcomes found an improvement in patient satisfaction [8]. The commonest mode of intervention delivery was classroom learning and was mostly provided to single healthcare worker occupations (i.e. nurses and doctors in isolation). Two studies performed follow-up measurements 3 to 4 weeks post-implementation and found higher cultural competence in the intervention group, but the long-term effects remain unclear.

Jongen and colleagues (2018) mapped characteristics of 64 cultural competency training interventions for Indigenous and racial minority groups across the US, New Zealand, Canada, and Australia, and highlighted two strategies [9].

First, a ‘categorical approach’ which focuses on teaching practitioners about the beliefs, values, behaviours, and appropriate response to different ethnic groups. And second, a ‘cross-cultural approach’ which focuses on teaching health care staff how to use general knowledge and skills to navigate variable cross-cultural situations [9]. The categorical approach to cultural competency training has been criticised because it risks over-simplifying culture, does not account for differences within cultural groups and may lead to stereotyping and increased cultural misunderstandings. The authors found both to be effective in improving staff’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but there was limited evidence of impacts on health and care outcomes.

LGBTQ+ focused cultural competency training

We found one review by McCann and colleagues (2023) that systematically assessed LGBTQ+ competency training for health professionals [10]. The authors found that across 44 studies cultural competency training improved 1) knowledge of LGBTQ+ culture and health, 2) skills to work with LGBTQ+ clients, 3) attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals, and 4) behaviours toward LGBTQ+ affirming practices. Interventions had more effect on knowledge rather than attitudes, suggesting that while healthcare workers may gain better awareness through competency training, it might not modify behaviours or bias against LGBTQ+ individuals.

Mental health focused cultural competency training

A review by Bhui and colleagues (2015) explored therapeutic communications between minority ethnic patients in a psychiatric setting [11]. Based on a review of 21 studies, the authors found evidence for improved outcomes when cognitive behavioural treatments and psychotherapies were culturally adapted. The review included 12 RCTs which demonstrated improvements in depressive symptoms; care experiences, knowledge, and stigma; adherence to prescribed medication; and insight and therapeutic alliance. The authors described how culturally competent care fits into a wider strategy to improve care: 1) preparing patients or professionals for their therapy, 2) enhancing and adapting existing therapies in terms of attention to cultural beliefs, and 3) influencing wider social systems (community agencies, family, social networks) before and during therapy.

Anti-racist training

Anti-racist training aims to educate health care staff on how racism operates and equip them with the tools to challenge racist attitudes, policies and practices [12]. Despite its importance, most cultural competency training does not routinely address racism or practitioner bias [9]. A review of 14 studies by Melro and colleagues (2023) found that addressing and teaching about colonialism in health outcomes for indigenous people was effective in changing health care workers’ attitudes and increasing knowledge immediately post intervention [13]. However, similarly to the studies on cultural competency training, Melro and colleagues questioned whether these behaviours translated into clinical practice, given the lack of monitoring of beliefs and attitudes over time and patient-reported outcomes.

Cénat and colleagues (2024) reviewed 30 studies examining anti-racist training programmes for mental health professionals [12]. The training focused on: 1) understanding the cultural, social, and historical context of mental health disorders; 2) developing awareness of self-identity and privilege; 3) recognising oppressive behaviours; and 4) building anti-racist competence in therapy and alternative approaches. Of the 10 studies that reported outcomes, all found positive outcomes, such as improved knowledge and attitudes, or reduced bias. However, no studies reported patient outcomes.

Anti-stigma training for staff towards people with mental illness

Wong and colleagues (2024) in a review of 25 studies found that educational interventions aimed at reducing stigma towards people with mental disorders were effective in improving healthcare professionals’ and students’ attitudes [14]. The educational interventions included lectures, workshops, online courses, simulations, role-playing and games. Subgroup analyses found that face-to-face interventions were more effective than online interventions, possibly due to the scope for tailored interactions and increased engagement. Interventions were similarly effective regardless of length of sessions.

Advocacy training

Scott and colleagues (2020) reviewed 78 studies aiming to characterise interventions for health advocacy education in postgraduate medical trainees [15]. The authors did not assess effectiveness of the interventions but found four types of interventions: 1) classroom-based interventions with or without a practical or interactive component; 2) clinical placements or practicals; 3) observations or ‘field trips’; and 4) interventions with both a classroom-based and clinical component. Key concepts that were covered more frequently included: adapting practice to respond to the needs of patients, communities, or populations served; advocacy in partnership with patients, communities, and populations served; determinants of health; health promotion; mobilising resources as needed; and social accountability of physicians.

Training for health professionals to support patients with low health literacy

Several studies have examined health literacy training for health professionals that aim to better support patients with low health literacy. These are covered in more detail in our complementary brief on What works to improve health and digital literacy in disadvantaged groups. In summary, studies primarily examined large group lectures and placements to help health care staff better understand patients with low health literacy [16]. The training was generally successful, with the more successful interventions offering numerous training sessions and integrated knowledge and skill acquisition, particularly when developed within real-world settings with patients or community members.

Health inequalities training through game-based interventions

Game-based training uses electronic games, board games or workshop-style games to enhance engagement and learning. It may be particularly effective in helping healthcare staff to understand the difficult choices that disadvantaged groups must make. Allan and colleagues (2024) reviewed 13 studies looking at game-based interventions to support health inequalities training in health care staff [17]. Eight studies examined table-top games, four studies examined electronic games, and one study examined both a table-top game and an electronic game. The authors found positive effects on staff learning, especially in terms of engaging staff in health equity concepts; however, patient outcomes were lacking. The heterogeneity between the training interventions made it difficult to compare.

2. Empowering through resources

Staff require the right tools to be empowered to address inequalities, such as adequate time, culturally competent resources, and models of care.

Adequate time

Without dedicated time, staff find it difficult to deliver equity-focused services. Brown and colleagues (2016) describe a quality improvement intervention to improve attendance at speech and language services for low-income families [18]. While attendance improved from 40–60% through a range of quality improvement initiatives to overcome barriers to attendance, the authors found that a key barrier to proactive follow up was competing job priorities among staff delivering the services.

In primary care, we know that GPs need more time to help patients with social problems. A study from 2007 in Manchester and London found that when GPs are asked to support patients with social issues, their appointments last about 15 minutes [19]. The standard 10-minute appointment in general practice is likely to limit the ability of GPs to support patients with complex social needs. However, research from 2021 suggests that GPs in the most deprived areas have shorter consultations, even after adjusting for health problems, compared to GPs in the least deprived areas [20].

Access to culturally competent and low health literacy resources

Staff need access to resources to support action on health inequalities; expecting staff to develop resources by themselves is likely to be a barrier. There are a few studies that have found positive benefits of providing staff with culturally competent resources. For example, Barceló and colleagues undertook a QI project that aimed to improve mental health outcomes in disadvantaged black and Latino adults [21]. Staff were provided with culturally competent care resources in English and Spanish throughout the project. Both groups experienced an improvement in mental health outcomes. However, there is evidence from the UK that simply translating English resources into other languages may create additional barriers. Aldosari and colleagues reviewed studies examining digital health literacy interventions for south Asians [22]. The authors found that when health information was translated into a patient’s first language, the writing style was often formal and often was a barrier to comprehension.

Trauma-informed care model

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a model of care that ‘is grounded in the understanding that trauma exposure can impact an individual’s neurological, biological, psychological and social development’ [23]. Brown and colleagues (2022) reviewed 10 studies involving TIC interventions in the emergency department (ED) and identified three key themes of effective TIC: 1) education, 2) collaboration and 3) safety [24].

- Seven studies with an educational component improved clinicians’ awareness and knowledge of TIC, but patient outcomes were lacking. They ranged from 15 minutes to eight hours and used activities such as face-to-face lectures, online modules, and standardised patient encounters.

- Eight studies included a collaboration component, partnering with other health professionals and community organisations, to support post-ED follow up and actions on the social determinants of health. Isolating the impact of collaboration on outcomes was not possible, but researchers of all studies reported that collaboration was important for intervention success.

- Six studies had interventions focused on patient or staff safety using TIC. The authors found that TIC was a core part of empowering staff through creating safe working environments. Safety included 1) precautions for patients’ emotional and physical wellbeing, 2) interventions to ensure staff safety and 3) plans for patients who have been identified as victims of violence.

3. Empowering through workforce structures

An authentically empowered and equitable workforce requires there to be staff from under-represented and diverse backgrounds at all levels of the organisation. This includes both recruiting diverse staff, enhanced professional development for traditionally underrepresented groups and retaining them in position. Furthermore, it requires roles and positions that help to empower staff.

Increasing the diversity of the workforce

There is limited research looking at interventions to diversify the workforce. Qureshi and colleagues (2020) undertook a review of interventions to widen participation in nursing for black and Asian minority ethnic men but were unable to find any studies [25].

A small study from 2005 showed that the NHS Cadet Scheme, a decommissioned programme that provided a route into nursing for people without sufficient qualifications or experience, increased the number of men and women from black and Asian backgrounds (from 2% and 1% to 7% and 4% respectively) [26].

There is more evidence for widening participation programmes in higher education. Two reviews from the US by McCord and colleagues (2024) and McNally and colleagues (2019) explored interventions aimed to increase and support diversity in nursing programmes and education [27][28] . Mentorship was the most common approach to increasing diversity in nursing programmes. This was the most effective at helping participants increase their grades or gain admission into such programmes, especially when provided culturally congruent mentors who can academically prepare under-represented students or raise awareness amongst their group. Most interventions were designed to influence admission or retention of nursing students from under-represented backgrounds. Scholarship was the next most common approach. McNally and colleagues also identified barriers, such as stereotyping and fear of stereotypes, which led to avoiding or not engaging in educational activities. In the UK, the Collaborative Targeted Outreach Programme in Luton sought to increase local south Asian residents to study nursing or midwifery at the University of Bedfordshire through outreach events in schools and a community event [29]. While quantitative outcomes are not available, participants reported positive attitudes and improved knowledge of the programmes. of the programmes.

In terms of diversifying medical specialities, Hemal and colleagues (2021) found 16 studies in the US examining interventions to increase diversity in surgical trainees [30]. The authors found that longitudinal mentoring of racial minorities increased the likelihood of applying for surgical residency.

Gkiouleka and colleagues (2024), in their case studies of hospitals as anchor institutions, included evidence on NHS Trusts supporting people from disadvantaged backgrounds into work [31]. The authors found evidence for in-person events, such as job fairs in community venues, open days, simplifying application forms and removal of criminal history at the initial stages of employment. See our complementary evidence brief for more details – What works: How health care organisations can reduce inequalities in social determinants of health in their role as anchor institutions.

Increasing diversity in senior positions

In 2012, Powell and colleagues reviewed NHS Talent Management schemes through interviews, focus groups and surveys [32]. The authors found that women and people from minority ethnic groups were more likely to report barriers to talent management schemes. Talent management schemes exist in the NHS to support underrepresented groups, such as the London Talent Management Support Network for minority ethnic nurses and midwives (see case study), but robust evaluation is lacking.

Zulfiqar and colleagues (2023) reviewed 62 studies examining talent management for internationally recruited nurses and found limited evidence [33]. The studies focused on recruitment, career progression, professional development and retention and found evidence that mentorship is critical for career development. Issues around cultural integration and communication were also noted to have significant impacts on international nurses’ work experience and their job satisfaction, underpinning the importance of cultural adaptation in designing effective talent management.

Retaining staff from underserved communities

Deroy and colleagues (2019) reviewed factors supporting retention of Aboriginal health and wellbeing staff in Australia [34]. A thematic analysis of 26 papers revealed five overarching facilitators for staff retention: cultural safety, teamwork and collaboration, supervision, professional development, and recognition. Cultural safety was described as non-Aboriginal staff being able to demonstrate culturally safe and sensitive practices when working alongside Aboriginal colleagues and their clients.

4. Empowering through staff roles

Health inequalities staff champions

We did not find any quantitative studies examining the impact of health care staff champions to promote health inequalities. A review of nine studies by Coverdale and colleagues (2024) examining end-of-life care for homeless adults found that homeless champions, palliative care specialists who advocate for better end-of-life care for people who are homeless, supported better partnership working and supported staff in hostels to develop a palliative care ethos [35]. A review by Wood and colleagues (2020) looked at clinical champions to promote the use of evidence-based practice in drug and alcohol and mental health settings [36]. The authors found that clinical champions helped with faster initiation and persistence over time, overcoming barriers, and staff engagement and motivation. Similarly, Santos and colleagues (2022) [37] reviewed the evidence and found that in 5 of 7 included studies champions helped with the adoption of best practice of technological innovations.

Case study: London’s Talent Management Support Network (TMSN) Programme [38]

In 2019, a talent management initiative was developed to support nurses and midwives from ethnic minorities throughout their career. The driver for the initiative was primarily based on data reported in the Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) that revealed nurses and midwives from minority ethnic backgrounds were more likely to face bullying and discrimination and less likely to progress in their professions compared to their white colleagues.

The aim was to support the development of staff’s talents through networking, specifically using action learning sets. The initiative was evaluated using online questionnaires and interviews. It revealed that the programme increased levels of confidence among participants, for example in terms of leading a shift, challenging bullying, or applying for promotion. Feedback from participants also led to programme changes such as changes to the length and duration of action learning set sessions and more flexible approaches to workshop design.

Limitations

Research on staff empowerment to address inequalities is limited to small scale studies and focuses on staff outcomes rather than patient outcomes. Workforce initiatives are difficult to evaluate because they operate in complex health care organisations and are traditionally under-researched. Where possible, we have used transferable evidence from other disciplines or fields but have not been able to do this exhaustively.

Measuring changes in cultural competence in health care staff was a common challenge [8][9]. Jongen and colleagues’ review, which primarily focused on the design and implementation of the interventions, also found that outcomes, such as patient satisfaction and clinical impact, were rarely examined. Furthermore, researchers seldom defined cultural competence in the context of intervention development [9]. This made comparison of studies difficult due to heterogeneity, limiting assessments of effectiveness.

What works: key recommendations

| Recommendation | Target audience | GRADE certainty |

Health care staff should undergo health equity training that covers:

|

NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies, and GP surgeries | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Health care organisations should ensure that staff have enough time to care for patients facing complex social circumstances and to undertake equity-focused service improvement projects. | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies, and GP surgeries | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Staff should have access to culturally competent resources and resources accessible to those with poor health literacy. | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies, and GP surgeries | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Trauma-informed care approaches should be promoted among staff, especially those in emergency departments and general practice. | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies, and GP surgeries | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Innovative learning models should be explored, such as game-based learning. | NHS England, ICBs and Trusts | ⊕ Very low |

| Healthcare organisations should develop programmes to diversify the workforce, especially mentorship in underrepresented specialities and senior leadership positions. | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, pharmacies, and GP surgeries | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

| Health care organisations should undertake outreach activities to help recruit people from socioeconomically disadvantaged areas in their local communities. | NHS England, ICBs, Trusts, pharmacies, and GP surgeries | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

*GRADE certainty communicates the strength of evidence for each recommendation.

Recommendations which are supported by large trials will be graded highest whereas those arising from small studies or transferable evidence will be graded lower. The grading should not be interpreted as priority for policy implementation – i.e. somerecommendations may have a low GRADE rating but likely to make a substantial population impact.

Useful links

How this brief was produced

What is the Living Evidence Map on what works to achieve equitable lipid management in primary care?

Using AI-powered software called EPPI-Reviewer, the Health Equity Evidence Centre has developed a Living Evidence Map of what works to address health inequalities in primary care. The software identifies research articles that examine interventions to address inequalities. The evidence map contains systematic reviews, umbrella reviews. More information can be found on the Health Equity Evidence Centre website.

Funding

This Evidence Brief has been commissioned by NHS England to support their statutory responsibilities to deliver equitable health care. Policy interventions beyond health care services were not in scope. DL is funded by NIHR ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of NHS England or NIHR.

Suggested citation

Ford J, Harasgama S, Lamb D, Dehn Lunn A, Gajria C, Painter H, Pearce H, Vodden A. Evidence brief: What works – Empowering health care staff to address health inequalities. Health Equity Evidence Centre; 2024

References

- Rolewicz L, Palmer B, Lobont C. Nuffield Trust. 2024. The NHS workforce in numbers [Internet].

Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/the-nhs-workforce-in-numbers - NHS England. NHS Workforce Statistics – November 2022 (Including selected provisional statistics for December 2022) [Internet]. 2023

Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/november-2022 - NHS Confederation. Key statistics on the NHS [Internet]. 2023.

Available from: https://www.nhsconfed.org/articles/key-statistics-nhs - NHS England. NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard 2023 data analysis report for NHS trusts [Internet]. 2023.

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-workforce-race-equality-standard-2023-data-analysis-report-for-nhs-trusts/ - NHS England. NHS Vacancy Statistics England, April 2015 – December 2023, Experimental Statistics [Internet]. 2024 Feb.

Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-workforce-statistics/november-2022 - YouGov UK. YouGov. 2024. NHS Workers Survey [Internet].

Available from: https://ygo-assets-websites-editorial-emea.yougov.net/documents/UK26552281_HealthcareProfessionals_W28_-_Internal.pdf - NHS England. General Practice Workforce Official Statistics [Internet]. 2024.

Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services - Duckhee C, Jinhee K, Suhee K, Jina L, Seojin P. Effectiveness of cultural competence educational interventions on health professionals and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Japan Journal Of Nursing Science. 2020;17(3).

- Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):232.

- McCann E, Brown M. The inclusion of LGBT+ health issues within undergraduate healthcare education and professional training programmes: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;64:204–14.

- Bhui K, Aslam R, Palinski A, McCabe R, Johnson Mark R, Weich S, et al. Interventions designed to improve therapeutic communications between black and minority ethnic people and professionals working in psychiatric services: a systematic review of the evidence for their effectiveness. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2015;19(31):1–174.

- Cénat Jude M, Broussard C, Jacob G, Kogan Cary S, Corace K, Ukwu G, et al. Antiracist training programs for mental health professionals: A scoping review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2024;102373.

- Melro C, Landry J, Matheson K. A scoping review of frameworks utilized in the design and evaluation of courses in health professional programs to address the role of historical and ongoing colonialism in the health outcomes of Indigenous Peoples. Advances In Health Sciences Education. 2023;28(4):1311– 31.

- Wong John Chee M, Chua Joelle Yan X, Chan Pao Y, Shorey S. Effectiveness of educational interventions in reducing the stigma of healthcare professionals and healthcare students towards mental illness: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2024;

- Scott MD, McQueen S, Richardson L. Teaching Health Advocacy: A Systematic Review of Educational Interventions for Postgraduate Medical Trainees. Acad Med. 2020;95(4):644–56.

- Saunders C, Palesy D, Lewis J. Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework for Health Literacy Training in Health Professions Education. Health Professions Education. 2019;5(1):13–29.

- Allan R, McCann L, Johnson L, Dyson M, Ford J. A systematic review of ‘equity-focused’ game-based learning in the teaching of health staff. Public Health in Practice. 2024;7:100462

- Brown CM, Beck AF, Steuerwald W, Alexander E, Samaan ZM, Kahn RS, et al. Narrowing Care Gaps for Early Language Delay: A Quality Improvement Study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015 May 20;55(2):137– 44.

- Popay J, Kowarzik U, Mallinson S, Mackian S, Barker J. Social problems, primary care and pathways to help and support: Addressing health inequalities at the individual level. Part II: Lay perspectives. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978). 2007 Dec 1;61:972–7.

- Gopfert A, Deeny S, Fisher R, Stafford M. Consultation length by multimorbidity and deprivation: observational study using electronic patient records. 2020.

- Barceló N, Lopez A, Tang L, Nunez M, Jones F, Miranda J, et al. Community Engagement and Planning versus Resources for Services for Implementing Depression Quality Improvement: Exploratory Analysis for Black and Latino Adults. Ethn Dis. 2019 Apr 18;29:277–86.

- Aldosari N, Ahmed S, McDermott J, Stanmore E. The Use of Digital Health by South Asian Communities: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e40425.

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. UK Government. 2022. Working definition of trauma-informed practice

Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-definition-of-trauma-informed-practice/working-definition-of-trauma-informed-practice - Brown T, Ashworth H, Bass M, Rittenberg E, Levy-Carrick N, Grossman S, et al. Trauma-informed Care Interventions in Emergency Medicine: A Systematic Review. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(3):334–44.

- Qureshi I, Ali N, Garcia R, Randhawa G. Interventions to Widen Participation for Black and Asian Minority Ethnic Men into the Nursing Profession: A Scoping Review. Diversity and Equality in Healthcare. 2020;17(2):107–14.

- Watson R, Norman IJ, Draper J, Jowett S, Wilson-Barnett J, Normand C, et al. NHS cadet schemes: do they widen access to professional healthcare education? J Adv Nurs. 2005 Feb 1;49(3):276–82.

- McCord A, Otte J. Interventions to Increase the Diversity of Nursing Programs: An Integrative Review. J Nurs Educ. 2024;63(6):387–93.

- McNally K, Metcalfe ES, Whichello R. Interventions to Support Diversity in Nursing Education. J Nurs Educ. 2019;58(11):641–6.

- Ali N, Cook E, Qureshi I, Sidika T, Waqar M, Randhawa G. The Collaborative Targeted Outreach Programme (CTOP): A Feasibility Intervention to Increase the Recruitment of ‘Home Grown’ South Asians onto Nursing and Midwifery Courses. Divers Equal Health Care. 2021 Aug 1;18:370–7.

- Hemal K, Reghunathan M, Newsom M, Davis G, Gosman A. Diversity and Inclusion: A Review of Effective Initiatives in Surgery. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(5):1500–15.

- Gkiouleka A, Munford L, Khavandi S, Watkinson R, Ford J. How can healthcare organisations improve the social determinants of health for their local communities? Findings from realist-informed case studies among secondary healthcare organisations in England. BMJ Open. 2024 Jul 1;14(7):e085398.

- Powell M, Durose J, Duberley J, Exworthy M, Fewtrell M, Macfarlane D, et al. Talent Management in the NHS Managerial Workforce.

- Zulfiqar SH, Ryan N, Berkery E, Odonnell C, Purtil H, O’Malley B. Talent management of international nurses in healthcare settings: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2023 Nov 6;18(11):e0293828

- Deroy S, Schütze H. Factors supporting retention of aboriginal health and wellbeing staff in Aboriginal health services: a comprehensive review of the literature. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):70

- Coverdale RM, Murtagh F. Destitute and dying: interventions and models of palliative and end of life care for homeless adults – a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024

- Wood K, Giannopoulos V, Louie E, Baillie A, Uribe G, Lee KS, et al. The role of clinical champions in facilitating the use of evidence-based practice in drug and alcohol and mental health settings: A systematic review. Implement Res Pract. 2020 Jan 1;1:2633489520959072.

- Santos WJ, Graham ID, Lalonde M, Demery Varin M, Squires JE. The effectiveness of champions in implementing innovations in health care: a systematic review. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3(1):80.

- Thomas V. Developing a talent management support network for nurses and midwives. Nurs Manage. 2023 Jun; 10.7748/nm.2023. e2085.