What works: How can integrated neighbourhood teams reduce inequalities in health and health care?

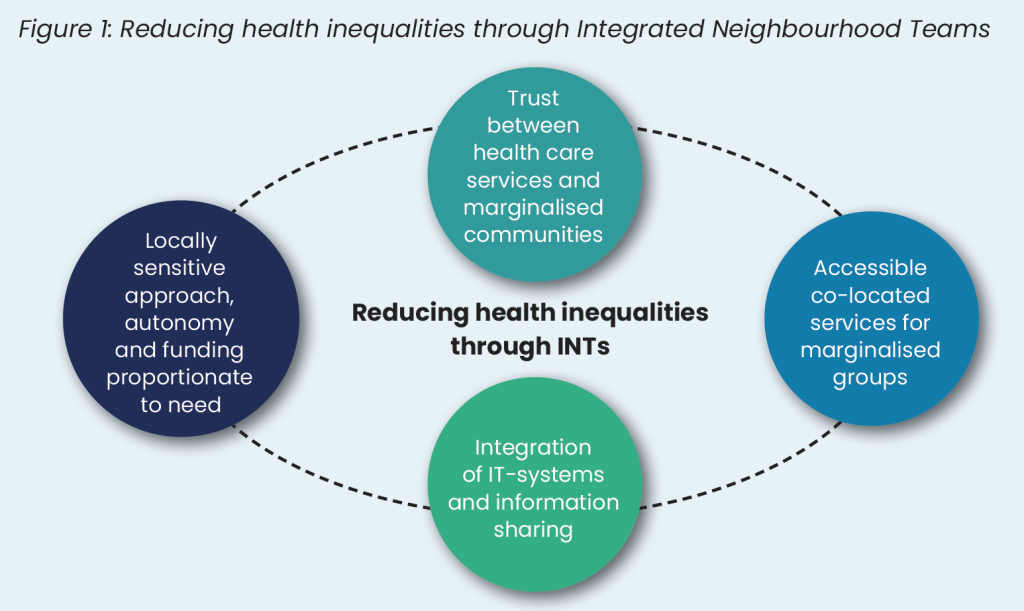

Integrated care can improve population health and reduce health inequalities. This brief highlights four key principles for designing INTs to reduce health inequalities based on the available literature and transferable evidence from studies on equitable primary care.

What works: How can integrated neighbourhood teams reduce inequalities in health and health care?[PDF 213kb]

Download documentSummary

Integrated care can improve population health and reduce health inequalities. The Fuller Stocktake recommended the establishment of Integrated Neighbourhood Teams (INTs) to improve access to a range of services, early prevention and continuity, in a joined-up approach. Evidence is still emerging in terms of the most effective models of care and how these could be used to address health and care inequalities.

In this brief, we discuss the learning coming from the available literature and the transferable evidence from studies on equitable primary care. Our review showed that there are four key principles that should inform the design and implementation of INTs to reduce health inequalities. These are:

- Locally sensitive approach, autonomy and funding proportionate to need

- Trust between health care services and marginalised communities

- Accessible co-located services for marginalised groups

- Integration of IT systems and information sharing

Current challenges

Health inequalities are forecasted to increase over the next two decades and people living in the poorest areas of the country are expected to receive a major illness diagnosis a decade earlier than those living in the most affluent areas [1]. Reversing these trends requires long-term effort across health and social care services, and local and national authorities [1]. In response, the NHS has committed to working with local authorities, communities, and the voluntary sector within integrated care systems (ICSs). ICSs aim to encourage multi-agency action to influence wider community and socioeconomic drivers of health and provide equitable health care services [2]. However, integrated care is complex involving a diverse range of services and care models, strategic priorities, and different levels of implementation [3]. While ICSs are responsible for system-wide integration of care involving strategic planning and resource allocation [4], improving the day-to-day care of individuals in an equitable way also requires hands-on multidisciplinary teams embedded within local communities and neighbourhoods [3].

The Fuller Stocktake, published in 2022, called for the setting up of Integrated Neighbourhood Teams (INTs) from current Primary Care Networks [5]. These ‘teams of teams’ caring for about thirty to fifty thousand people would blend specialist and generalist care with community organisations to improve access, continuity and prevention in a joined-up manner. Several local areas have already developed integrated neighbourhood teams, but there is substantial variation in their form and function.

Situating integrated care services within local communities and neighbourhoods (i.e., local communities of about thirty to fifty thousand people) has the potential to address health inequalities and contribute to a more efficient and cost-effective health system [5]. The recent report on the state of the NHS [6] reiterated this message. It highlighted that repairing the system and improving population health requires a shift towards a neighbourhood NHS with multidisciplinary models of care that combine primary, community and mental health services. However, evidence on integrated neighbourhood teams is scarce and rarely includes an inequalities angle. At the neighbourhood level, local evaluations in the UK suggest that most often INTs aim to address the needs of older frail patients or people with multimorbidity and other vulnerabilities [3][7][8]. However, as INTs evolve there is a need to consider the ways in which they can support a reduction in health inequalities [7]. Here we aim to identify the key principles that should inform the design and delivery of INTs so they can play their role in addressing health and care inequalities.

Summary of evidence

We searched for literature focusing on the impact of integrated neighbourhood approaches to care on health inequalities through the Living Evidence Maps of the Health Equity Evidence Centre. We identified only five studies, four of which were qualitative, and one was an evaluative review. Additional searches in PubMed and Google Scholar generated 17 additional studies, the majority of which did not focus on inequalities but offered useful insights regarding the facilitators and barriers to effective integrated neighbourhood or community care teams. In addition, where there was a paucity of evidence, we used transferable learning from our complementary evidence briefs.

Our review showed that there are four key principles that should inform the design and implementation of INTs to reduce health inequalities. These are:

- Locally sensitive approach, autonomy and funding proportionate to need

- Trust between health care services and marginalised communities

- Accessible co-located services for marginalised groups

- Integration of IT systems and information sharing

Locally sensitive approach, autonomy and funding proportionate to need

Although INTs are a care model for all adults, until now they have been mostly used to support older, frail individuals [5][9]. To ensure that INTs address inequalities they need to adopt a localised approach that addresses the needs of specific groups that experience inequalities. Evidence from research in primary care shows that a locally sensitive strategy that accounts for differences within populations is key for delivering equitable care [10][11]. INTs with their focus on local communities of about thirty to fifty thousand people [5] are in an advantageous position to do this. Identifying groups who experience inequities in their catchment area enables INTs to target their efforts and tailor their work accordingly to the needs and preferences of those groups [11]. This is why a locally sensitive approach is key.

However, developing a locally sensitive approach requires context-specific targets, strategy and implementation plans which in turn require flexibility and autonomy. To tailor care to the needs of groups who experience inequalities in their catchment area, INTs need to autonomously decide their approach, the desired outcomes and relevant indicators, as well as the resources needed to achieve these outcomes. This inevitably means that INTs will not necessarily involve the same services across all contexts, and they will differ in terms of day-to-day operations, workforce, and communication modes [3]. Evidence shows that the autonomy of INTs can foster the sense of trust between service providers and users [7][12] which further benefits the engagement of disadvantaged groups with available care and support. Moreover, autonomy at neighbourhood level allows for greater flexibility in service delivery. This in turn creates more space for equitable care through a holistic model that can accommodate for differences among service users including the more disadvantaged [13].

Aiming for locally sensitive approaches that address inequalities and flexibility in care design and delivery doesn’t come with a standard cost. Addressing local need requires funding and resources proportionate to this need. Previous research has highlighted how allocating health care funding proportionate to need can reduce inequalities in health care amenable mortality [14]. Upcoming research suggests that a new district nurse staffing allocation model can ensure that health care resources are distributed more accurately and equitably at the neighbourhood level [15]. The study shows that key need predictors for district nursing services include age, deprivation, chronic diseases, neurological disease, mental ill health, learning disability, living in a nursing home, living alone and receiving palliative care. The need is highly weighted towards older and more deprived populations. However, currently the distribution of staff correlates more with age rather than deprivation. The authors suggest that shifting to a needs-based staffing distribution at the neighbourhood level has the potential to reduce inequalities.

Still, a balance is needed between autonomous neighbourhood level approaches and the establishment of a common INT framework to support development and evaluation [3]. Aligning INTs with national health inequalities frameworks (e.g. the Core20PLUS5) and sharing learning and concerns among service providers, communities, and decision makers can ensure that this balance is achieved [3][12].

Trust between health care services and marginalised communities

A realist review of health inequalities interventions in general practice showed that equitable care is more possible when everyone involved in care – health care professionals, patients, their families, and communities – engages with care design and delivery [10]. They highlighted that addressing the need of disadvantaged patients requires investing in a sense of community where disadvantaged patients and their communities have a voice and participate in decision-making and programme implementation. However, meaningful engagement of communities, especially those systematically marginalised within care services requires relationships of trust [10]. During the Covid-19 pandemic, we saw that trust in health care services was crucial for tackling vaccination hesitancy among some ethnic minority groups and disadvantaged communities [16]. We also saw the difference it makes when general practitioners are trusted within the communities and work together with faith and other grassroots leaders [17].

Qualitative US studies on the effectiveness of INT approaches in addressing health inequalities show that tailoring care models to the needs of local groups who experience inequalities is only achieved through an open dialogue between professionals and patients on health improvement, priority setting and decision making [18]. Building trust among providers, patients and their communities takes time and consistent effort but it is fundamental for such a dialogue [19][20]. In one of the studies, researchers conducted focus groups with 100 participants, predominantly from African American and Latinx communities [20]. They found that the focus groups enabled these communities to speak openly about the social barriers they experienced in accessing care or managing their health and to suggest their own ways to address those barriers.

According to the reviewed literature [18]–[21], ways to establish trust and engage disadvantaged communities in the development of a neighbourhood-based strategy involve:

- outreach methods (i.e. proactive contact in the living environment of people)

- delivering prevention services in familiar and accessible community venues

- continuity in general practice

- interviews with individual community members in a safe and familiar context

- group-listening sessions facilitated by community members

- collaboration with community advisory groups, faith organisations and spiritual leaders, and charities

- involving family members, formal and informal carers in care delivery

- general practitioners and other health care providers regularly attending community events, local forums, and networks.

Accessible co-located services for marginalised groups

Proximity of care and co-located services are two distinct features of INTs that are important in meeting the needs of disadvantaged patients and reducing health inequalities [5]. Co-location of complementary health services (e.g., specialty mental health services co-located in primary care) together with welfare and/or legal aid services can make access and engagement with care easier for people from poorer areas and minority ethnic groups [5]. It can also directly mitigate the impact of inequalities in the social determinants of health [10] and enables the comprehensive assessment of patients’ unmet social and health needs [18][19][20][22]. Co-location reduces both the distance and the effort needed to engage with services [23][24][25]. It can also protect patients from stigmatisation associated with the use of certain services.For example co-locating mental health interventions in communities has been found to create non-judgemental environments that reduce stigma and improve access and engagement for disadvantaged patients [26][27]. These factors drive better access to access to services and improved patient adherence to treatment plans [23][24][25].

Welfare and legal advice services co-located in primary care have been also found to improve mental health and psychological wellbeing outcomes including reductions in symptoms of depression and anxiety, sleep problems and substance misuse among disadvantaged patients [9][25][28]. Additionally they improve the financial circumstances of service users through enabling access to available support and benefits [9]. Qualitative studies focusing on INTs highlight that bi-directional referrals within INTs ensure seamless support delivery and improve service users’ experience who value having somebody to advocate for them [18][22].

Additional evidence shows that co-located primary and specialist health care, social and legal support services maximise the knowledge and capacity shared within teams and empower staff to engage with issues that go beyond their usual scope (e.g. addressing social determinants of health) [9][28]. However, professional and social hierarchies within INTs can create tensions as happens in any other context [10]. A report on the integration of health and social care at a neighbourhood level in Manchester highlights some of these tensions [12]. The findings show that social care staff felt anxiety around the domination of health care, and professionals in the community services felt neglected by acute health services. At the same time differences between professionals’ terms and conditions often hindered integration. Empowering staff to engage with the power dynamics in their teams [13] is important and cultivates a context of psychological safety. Effective communication that suits everyone’s needs [12], fostering local networks, (e.g. between primary care professionals, social workers, civil society), and valuing participation and shared ownership [21] are all important ways to cultivate mutual relationships and trust among professionals.

Integration of IT systems and information sharing

Integrated IT systems and information sharing across different providers in INTs is key both for the effectiveness of integration and addressing health inequalities. Evidence from two large review studies in primary care [9][10] highlights the importance of maintaining up-to-date patient registers, including health and socio-demographic data, as a key step in identifying patients with unmet needs. Complete patient records enable systematic flagging and identification of individuals vulnerable to health inequalities in prevention and long-term condition management.

Patient and service information also needs to be shared across different professionals within INTs. This requires good integrated information systems across sectors (e.g., primary/specialist and social care) and that all providers involved in an INT are confident about accessing and using these systems [12]. Duplicate processes and fragmented care create gaps through which disadvantaged patients often fall – for example, when they must repeatedly share their story with different professionals or complete multiple forms [3][9]. It is therefore particularly important for these patients that the care and support provided within INTs is as seamless as possible. Finally, supporting vulnerable patients often entails navigating safeguarding and risk assessment challenges. When information is inconsistent across governance protocols, INT staff may feel anxious about patient privacy and hesitant to access or share information. This hesitation can result in delays and missed opportunities to deliver appropriate support to vulnerable patients [11].

Limitations

Evidence discussed in this brief is limited because INT is an emerging care model and there is limited evidence regarding its effectiveness and impact on inequalities or specific disadvantaged communities. The evidence discussed comes from international academic literature and some UK based reports that describe different models and definition of INT schemes.

Recommendations

| Recommendation | Target audience | GRADE certainty |

| Develop effective formulas for resource distribution according to need at the neighbourhood level | ICBs and NHS England | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Use community partnerships to identify groups with unmet needs in the neighbourhood | Integrated Neighbourhood teams, PCNs, General practices, VCSE and ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Foster partnerships of trust among services and marginalised communities in the neighbourhood and co-decide about health needs, priorities, and effective action | Integrated Neighbourhood teams, PCNs, General practices, VCSE and ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Commit to national guidance about accessible registration to general practice and ensure flexible access pathways according to local needs | Integrated Neighbourhood teams, PCNs, General practices, and ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Co-locate primary care and mental health services with legal aid and social care support | Integrated Neighbourhood teams, PCNs, General practices, and ICBs | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

*GRADE certainty communicates the strength of evidence for each recommendation.

Recommendations which are supported by large trials will be graded highest whereas those arising from small studies or transferable evidence will be graded lower. The grading should not be interpreted as priority for policy implementation – i.e. some recommendations may have a low GRADE rating but likely to make a substantial population impact.

How this brief was produced

Using AI-powered software called EPPI-Reviewer, the Health Equity Evidence Centre has developed a Living Evidence Map of what works to address health inequalities in primary care. The software identifies research articles that examine interventions to address inequalities. The evidence map contains systematic reviews, umbrella reviews. More information can be found on the Health Equity Evidence Centre website.

Suggested citation

Gkiouleka A, Malo L, Clark E, Dehn Lunn A, Engamba S, Gajria C, Loftus L, Torabi P, Ford J. Evidence brief: What works – How can integrated neighbourhood teams reduce inequalities in health and health care? Health Equity Evidence Centre; 2025

References

- Health inequalities in 2040 – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28].

Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/health-inequalities-in-2040 - NHS England » Our approach to reducing healthcare inequalities [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 28]

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/our-approach-to-reducing-healthcare-inequalities/ - George T, Horner N, McKay S, Ray M, Walker J. Developing a programme Theory of Integrated Care: the effectiveness of Lincolnshire’s multidisciplinary Neighbourhood Teams in supporting older people with multi-morbidity (ProTICare) [full report] [Internet]. University of Lincoln; 2017 Jul [cited 2024 Oct 14].

Available from: https://repository.lincoln.ac.uk/articles/report/Developing_a_programme_Theory_of_Integrated_Care_the_effectiveness_of_Lincolnshire_s_multidisciplinary_Neighbourhood_Teams_in_supporting_older_people_with_multi-morbidity_ProTICare_full_report_/24366232/1 - NHS England » What are integrated care systems? [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 10].

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/what-is-integrated-care/ - NHS England. Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller Stocktake report [Internet]. 2022 May [cited 2024 Oct 10].

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/next-steps-for-integrating-primary-care-fuller-stocktake-report.pdf#page=3.66 - Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England.

- NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. Understanding and supporting the integration of health and social care at a neighbourhood level in the City of Manchester -Part A [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 14].

Available from: https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/media/Resources/OHC/CLAHRC%20GM%20Manchester%20Integration%20report%20Part%20A%20final.pdf - Leask CF, Gilmartin A. Implementation of a neighbourhood care model in a Scottish integrated context—views from patients. AIMS Public Health. 2019 Apr 17;6(2):143–53.

- Johnson DY, Asay S, Keegan G, Wu L, Zietowski ML, Zakrison TL, et al. US Medical-Legal Partnerships to Address Health-Harming Legal Needs: Closing the Health Injustice Gap. J GEN INTERN MED. 2024 May 1;39(7):1204–13.

- Gkiouleka A, Wong G, Sowden S, Bambra C, Siersbaek R, Manji S, et al. Reducing health inequalities through general practice. The Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(6):e463–72.

- Jackson B, Ariss S, Burton C, Coster J, Reynolds J, Lawy T. The FAIRSTEPS Study: Framework to Address Inequities in pRimary care using STakEholder PerspectiveS—short report and user guidance. 2023.

- NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Greater Manchester. Understanding and supporting the integration of health and social care at a neighbourhood level in the City of Manchester -Part B [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 18].

Available from: https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/media/Resources/OHC/MInt%20Report%20-%20May%202019.pdf#page=17.99 - Gkiouleka A, Wong G, Sowden S, Kuhn I, Moseley A, Manji S, et al. Reducing health inequalities through general practice: a realist review and action framework. Health and Social Care Delivery Research. 2024;12(7).

- arr B, Bambra C, Whitehead M. The impact of NHS resource allocation policy on health inequalities in England 2001-11: longitudinal ecological study. BMJ. 2014 May 27;348:g3231.

- Filipe L, Piroddi R, Baker W, Rafferty J, Buchan I, Barr B. Improving equitable healthcare resource use: Developing a neighbourhood district nurse needs index for staffing allocation [Internet]. Research Square; 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 31].

Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4431791/v1 - Razai MS, Osama T, McKechnie DGJ, Majeed A. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority groups. BMJ. 2021 Feb 26;372:n513.

- Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine uptake among minority ethnic groups.

- Malika N, Herman PM, Whitley M, Coulter I, Maiers M, Chesney M, et al. Qualitative Assessment CIH Institutions’ Engagement With Underserved Communities to Enhance Healthcare Access and Utilization. Glob Adv Integr Med Health. 2024 Mar 26;13:27536130241244759.

- García AA, West Ohueri C, Garay R, Guzmán M, Hanson K, Vasquez M, et al. Community engagement as a foundation for improving neighborhood health. Public Health Nursing. 2021;38(2):223–31.

- García AA, Jacobs EA, Mundhenk R, Rodriguez L, Pulido CL, Hall T, et al. The Neighborhood Health Initiative: An Academic–Clinic–Community Partnership to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2022;16(3):331–8.

- De Donder L, Stegen H, Hoens S. Caring neighbourhoods in Belgium: lessons learned on the development, implementation and evaluation of 35 caring neighbourhood projects. Palliat Care. 2024 Jan 1;18:26323524241246533.

- van Ens W, Sanches S, Beverloo L, Swildens WE. Place-Based FACT: Treatment Outcomes and Patients’ Experience with Integrated Neighborhood-Based Care. Community Ment Health J. 2024 Aug;60(6):1214–27.

- Reece S, Sheldon TA, Dickerson J, Pickett KE. A review of the effectiveness and experiences of welfare advice services co-located in health settings: A critical narrative systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2022 Mar;296:114746.

- Young D, Bates G. Maximising the health impacts of free advice services in the UK: A mixed methods systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022 Sep;30(5):1713–25.

- Beardon S, Woodhead C, Cooper S, Ingram E, Genn H, Raine R. International Evidence on the Impact of Health-Justice Partnerships: A Systematic Scoping Review. Public Health Rev. 2021 Apr 26;42:1603976.

- Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why Are Some Population Interventions for Diet and Obesity More Equitable and Effective Than Others? The Role of Individual Agency. PLoS Med. 2016 Apr;13(4):e1001990.

- White M, Adams J, Heywood P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? In: Social inequality and public health [Internet]. Policy Press; 2009 [cited 2024 Jun 14]. p. 65–82.

Available from: https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/edcollchap/book/9781847423221/ch005.xml - Jomaa D, Ranasinghe C, Raymer N, Leering M, Bayoumi I. The Impact of Medical Legal Partnerships: A Scoping Review. University of Toronto Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 30];3(2).

Available from: https://utjph.com/index.php/utjph/article/view/38094