What works: Leveraging Quality Improvement to address health and care inequalities

Quality improvement (QI) seeks to enhance care but does not consistently consider equity, leading to potential intervention-generated inequalities. This brief summarises the evidence on what works to ensure that QI addresses inequalities, categorising approaches that improve or worsen them.

What works: Leveraging Quality Improvement to address health and care inequalities[PDF 224kb]

Download documentSummary

Quality improvement (QI) is a data-driven approach to improve care. The NHS undertakes thousands of QI programmes each year, ranging for small clinical audits to national improvement programmes. Quality health care should be equitable, but equity is not consistently considered in QI projects. This can drive intervention-generated inequalities where improvements are inadvertently targeted to those experiencing more privilege within the system, widening the gap. QI has the potential to address inequalities through 1) ensuring an equity perspective in existing QI, 2) undertaking new QI projects focused on disadvantaged groups, or 3) using QI methodologies within existing health inequalities programmes to incrementally narrow inequalities.

Here we present a review of the literature on what works to ensure that QI addresses inequalities. Based on a review of 36 studies, we divide the literature into QI approaches that are likely to improve inequalities and those which are likely to worsen inequalities.

QI that is likely to improve inequalities should:

- Where possible, leverage health care staff’s moral imperative to address inequalities complemented by implicit bias training and promoting a wider determinants of health approach.

- Facilitate dedicated time for staff to develop equity focus within QI and provide easy access to multilingual and culturally competent resources.

- Use diverse quantitative and qualitative data and routinely disaggregate data by disadvantaged groups.

- Embed co-creation of QI initiatives with a diverse range of service users and staff groups.

QI that is likely to worsen inequalities would:

- Focus on equality (providing the same care to everyone), rather than equity (providing care based on need)

- Expect staff with unmanageable workloads or lack of an understanding of diverse patient circumstances to consider inequalities in QI

- Make it difficult to gain insights on disadvantaged groups from the electronic patient record

- Design QI initiatives that require considerable patient effort to benefit, such as understanding health information, digital literacy and access, or good access to transport.

Current challenges

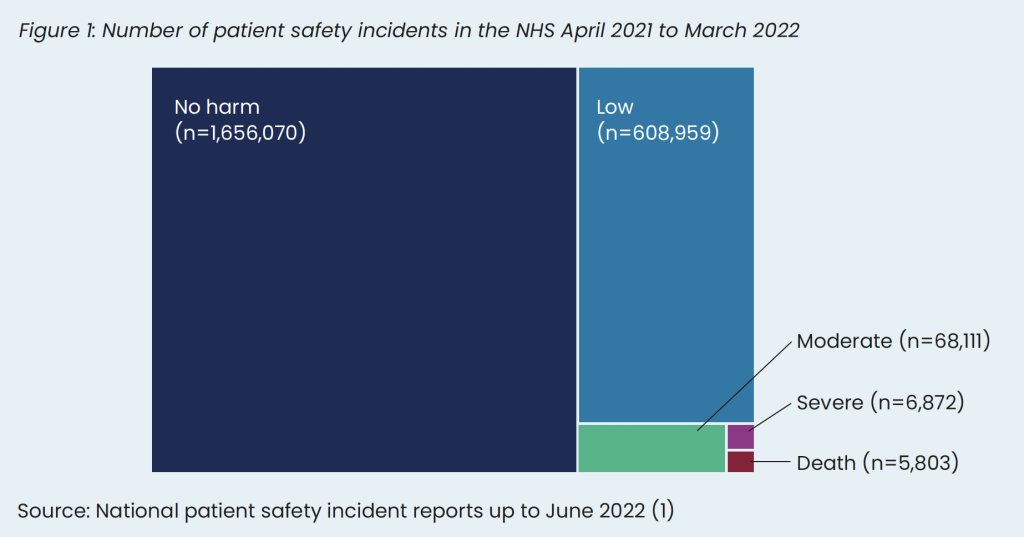

Almost 6,000 people die in the NHS every year in England because of patient safety incidents, reflecting issues in quality of care (see Figure 1) [1]. Most of these deaths occur in hospitals (43%) or mental health services (41%). The actual number is likely to be higher because of under-reporting, with some previous research suggesting that it is closer to 11,000 deaths per year in English hospitals [2]. Patient safety reporting in general practice is also known to be under-reported [3]. We do not have disaggregated data by ethnicity or socioeconomic status; however, a recent review of 45 international studies, including two from the UK, found that, compared to the general population, people from ethnic minority communities had higher rates of hospital acquired infections, complications, adverse drug events, and dosing errors [4]. Underlying reasons included language proficiency, beliefs about illness and treatment, formal and informal interpreter use, community engagement, and interactions with health professionals.

The NHS undertakes thousands of QI initiatives each year to improve health care and outcomes. QI initiatives, including clinical audit, are considerably heterogenous across the NHS – ranging from individual clinicians implementing small changes to improve care processes in a single ward or GP surgery to large hospital-wide programmes. QI is an umbrella term and encompasses many activities, however generally these initiatives usually involve multiple feedback loops to continuously and incrementally improve and maintain good health care. There are numerous QI frameworks that exist, such as Plan-Do-Study-Act and the Model for Improvement [5].

The NHS invests significantly in embedding QI training and programmes across services, including implementing the Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign (QSIR) programme to increase the quantity and quality of QI across the NHS [6].

Definitions

Quality improvement (QI): Systematic, data-guided activities designed to bring about an immediate improvement in health care delivery in particular settings [7].

Equity-focused quality improvement: QI initiatives that integrate equity throughout the fabric of the project and are inclusive, collaborative efforts that prioritise and address the needs of disadvantaged populations [8].

Most definitions of health care quality include equity, such as the Institute of Medicine’s six domains of quality (safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient and equitable) [9]. However, equity is not an explicit part of most QI programme methodologies, and QI can unintentionally widen health inequalities [10]. For example, the introduction of continuous glucose monitoring for children with type 1 diabetes led to an increase in inequalities. The National Paediatric Diabetes Audit in England and Wales found that continuous glucose monitors improved the quality of care, improving HbA1c by 2.6mmol/mol. However, this benefit was not equally distributed – children in the most deprived areas had a 3 times smaller improvement compared to children in the least deprived areas [11].

The potential for quality improvement to address health and care inequalities is substantial and covers three main areas.

- Shifting the thousands of QI initiatives which are undertaken in the NHS to consider inequalities – the NHS undertakes a huge number of QI initiatives every year and supporting these projects to consider inequalities has the potential to ensure QI benefit those with the greatest need.

- Undertaking new QI projects which specifically focus on closing the gap or targeting specific disadvantaged groups – well-known inequalities exist in certain NHS services, such as maternity care [12], and some groups persistently receive poor care, such as people in prison [13]. Targeting QI initiatives to services with known inequalities or groups experiencing poor care has the potential to address inequalities.

- Use of QI techniques within existing health inequalities programmes to optimise outcomes – NHS organisations across the country are implementing a range of health inequalities programmes, many based on the Core20PLUS5 framework [14]. QI techniques may help to continually improve the impact of these health inequalities programmes through a data-driven and systematic approach with continual feedback.

Here we review the evidence examining how quality improvement techniques can be used to address health and care inequalities.

Summary of evidence

We undertook a search of electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Web of Science, and SCOPUS) to identify quality improvement programmes that also reported on health and care inequalities. We included 36 studies, most of which were from North America, with five from the UK, focusing on ethnic minority groups, socioeconomic status, or gender inequalities.

Quality improvement initiatives are dependent on the settings (e.g. primary versus secondary care) and population groups (e.g. people on low incomes versus ethnic minority groups). Therefore, it is not possible, or desirable, to combine several studies to estimate the overall impact of QI on health inequalities. We have therefore identified common principles in the data explaining how QI initiatives could be used to address health and care inequalities.

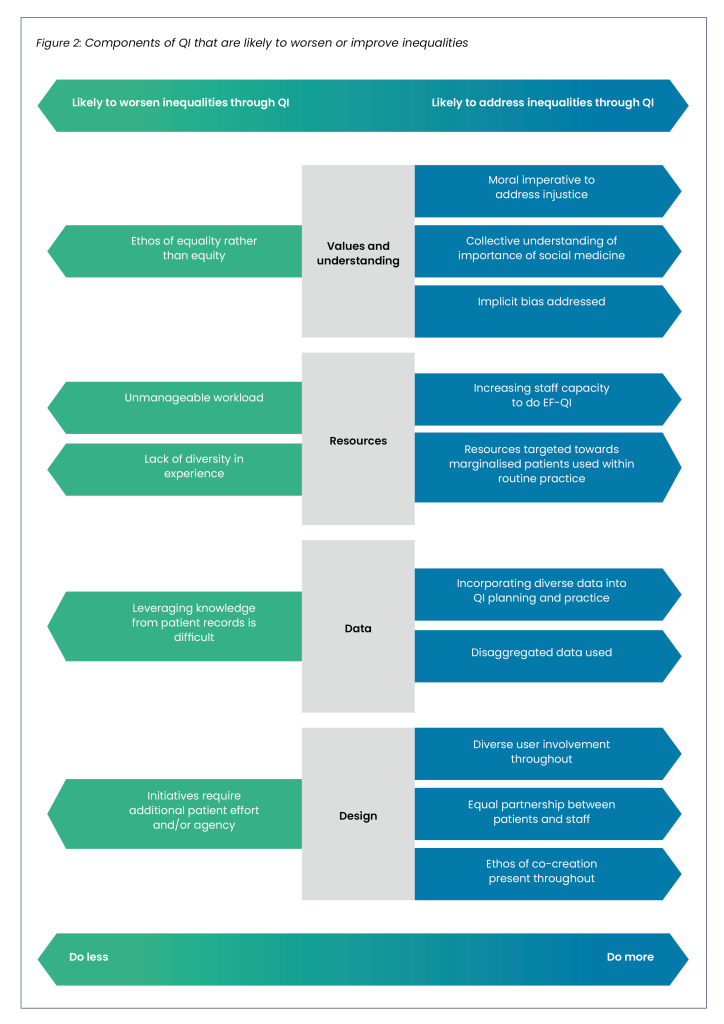

Based on the evidence, we identified components of QI that are likely to worsen inequalities and those which are likely to improve inequalities (see Fig. 2).

QI that is likely to improve inequalities should:

- Where possible, leverage health care staff’s moral imperative to address inequalities, complemented by implicit bias training and promoting a wider determinants of health approach.

- Facilitate dedicated time for staff to develop equity focus within QI and provide easy access to multilingual and culturally competent resources.

- Use diverse quantitative and qualitative data and routinely disaggregate data by disadvantaged groups.

- Embed co-creation of QI initiatives with a diverse range of service users and staff groups.

QI that is likely to worsen inequalities would:

- Focus on equality (providing the same care to everyone), rather than equity (providing care based on need).

- Expect staff with unmanageable workloads or lack of understanding of the diverse patient circumstances to consider inequalities in QI.

- Make it difficult to gain insights on disadvantaged groups from the electronic patient record.

- Design QI initiatives that require considerable patient effort to benefit, such as understanding health information, digital literacy and access, or good access to transport.

Harnessing the values of health care staff

Based mainly on US studies focused on racial inequalities in health care, projects that were based on a strong moral imperative to address injustices were more likely to address inequalities. These studies highlight the importance of pre-existing staff values, often arising from historical social injustices, that can be leveraged to help tackle existing inequalities [15]–[25]. For example, Burkitt and colleagues examined a programme of QI activities, such as staff education and audit and feedback loops, to reduce inequalities in blood pressure control among black veterans [16]. Inequalities in hypertension across ethnic groups narrowed, partly because there was an explicit value judgement among staff that ethnic inequalities were wrong, and they could take action to restore a degree of justice. However, the QI leaders faced challenges from some staff who questioned the ethics of targeting hypertension resources specifically at the black veteran population, rather than all veterans equally.

This highlights the tensions between equality in health care provision (equal provision of services irrespective of background) and equity in QI projects (everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible). An ethos of equality of health care provision, rather than health equity, could be a barrier to allocating resources proportionate to need.

In some QI initiatives within the literature, there was an acknowledgement of how the social determinants of health created barriers for some people to benefit from the QI. For example, Meurer and colleagues examined a QI project in 25 paediatric clinics to improve developmental screening through clinic champions, staff training, standardising tools, electronic record prompts, and feedback loops [26]. Screening rates improved from 60% to over 95%, but socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities widened. The authors reflected that more cross-sector collaboration, especially with education and partnerships with community agencies to support the social determinants of health, would have helped limit the impact on health inequalities.

QI initiatives and programmes that were effective in addressing inequalities often included staff training on implicit bias and institutional racism. For example, Cykert and colleagues found that a QI programme reduced ethnic inequalities in cancer treatment completion rates from 8% difference between black and white groups to 1% difference after the QI programme [18]. The team used a registry of participants who had missed appointments or had unmet care milestones, a community navigator, and clinical feedback. High-quality staff and navigator training on racism and implicit bias was reported to be a key component through regular sessions, case-based approaches and drawing on validated training programmes.

Ensuring staff have sufficient time and access to culturally tailored resources

Based on the included studies, we identified two key themes related to resources: first, the need to ensure staff have sufficient capacity, and second, improving access to multilingual resources. These themes complement the evidence gathered for our Empowering health care staff to address health inequalities evidence brief.

QI initiatives associated with success often included giving staff dedicated time to consider equity in QI and avoid it becoming a ‘tick box exercise’. There are examples in the literature of the negative impact that competing responsibilities have on staff who would like to consider equity in QI. For example, Brown and colleagues found that using the Model for Improvement improved care for early language delay in families on low incomes (increase from 40% to 60% in attendance at initial appointments within 60 days) [27]. However, staff members reported competing job responsibilities as a key factor in preventing adequate follow up. Disadvantaged groups often require more proactive follow up due to social problems meaning that staff are more likely to follow up those who are easier to contact and also tend to be more affluent.

QI initiatives that provided staff with multilingual resources specifically for marginalised groups along with cultural competency training were effective in improving care for disadvantaged groups. For example, Barceló and colleagues undertook a QI project that aimed to decrease inequalities and improve mental health outcomes in Black and Latino adults [28]. Throughout the project, materials were provided both in English and Spanish, and culturally competent care principles and resources built into interventions. Black and Latino adults experienced an improvement in mental health outcomes.

On the other hand, when staff lacked the training, experience, and exposure to diverse groups with different health needs, they were more likely to undertake QI projects designed with the idea of an ‘average’ patient in mind. For example, Cene and colleagues evaluated a QI project aimed at reducing racial disparities in blood pressure management between African American and white patients [17]. While there were improvements in both groups, white patients had the greatest improvement (reduction of systolic BP of -7.8 mmHg versus -5.0 mmHg). The authors reflected that a lack of cultural tailoring and failure to appreciate the unique factors that influence hypertension in African American people likely contributed to the worsening of inequalities.

Leveraging data to understand and address inequalities

The basis of several QI projects was incorporating disaggregated data by disadvantaged groups into feedback loops, such as PDSA cycles. Stratifying data by subpopulation allows QI practitioners to identify those with the worst outcomes, allowing insights into existing and emerging inequalities and more focused targeting of QI projects. For example, Davidson and colleagues evaluated a QI programme to reduce ethnic inequalities in maternal morbidity due to haemorrhage [19]. The QI programme used stratified data throughout, complemented by a range of initiatives, such as in-depth case reviews and guideline development, and the authors found a reduction in baseline inequalities, including a reduction in the rate of haemorrhage in black women from 46% to 32%.

However, the effective use of data can be hindered when accessing information from electronic patient records is difficult or does not allow disaggregation. For example, Gagnon and colleagues qualitatively evaluated a QI programme to improve healthcare for sexual and gender minority patients [29]. The authors found that the electronic patient record was the most common barrier to QI implementation. Staff struggled to obtain data and had issues incorporating new fields into the electronic patient record, which meant identifying and monitoring target populations was challenging; all of which was compounded by a lack of IT support.

Designing QI programmes to address inequalities and not worsen them

The QI design process can substantially impact inequalities. This ethos of co-creation with both diverse communities and multidisciplinary staff groups was a strong theme in several studies focused on using QI to address inequalities [23][28][30]–[35]. For example, Green and colleagues undertook a QI programme to improve physical health checks for patients admitted to an acute mental health unit [34]. The authors found a 16% increase in physical health checks and attributed the success to 1) assembling a multidisciplinary team of a senior psychologist and psychiatrist, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, including a fitness trainer and senior management, and 2) service user involvement using the 4PI Framework developed by the National Survivor User Network. Active involvement of service users and front-line clinical staff in co-producing the QI interventions was reported as fundamental to success. Furthermore, Greenwood and colleagues found an improvement from 10% to 80% in cardiovascular assessments in people with severe mental illness using a QI programme. The authors found that service user involvement was ‘crucial’ to its success, helping to establish ‘an ethos for improvement; one of candour and collaboration’ [32].

QI initiatives may also inadvertently increase inequalities in the way they are designed. For example, QI projects that require a substantial amount of effort and resources from patients to benefit risk worsening inequalities because patients with complex social and health needs are less likely to take part. For example, Brown and colleagues, in their QI programme to improve care for language delay in children, found that offering patients same-day appointments increased inequalities in the post-intervention period because of difficulties for some in arranging transport at short notice [27].

Limitations

We found numerous examples of QI programmes that have successfully reduced health inequalities. It is unlikely that there is one common intervention or initiative that can be implemented to guarantee success. The impact of factors, such as culture and leadership, are rarely described in the QI inequalities literature but are likely to have a significant impact. Furthermore, organisational transformation in complex health care systems requires multicomponent action across multiple levels. Therefore quantifying evidence on single QI initiatives is likely to be misleading without considering their interaction with the health care setting and other programme components.

What works: key recommendations

| Recommendation | Target audience | GRADE certainty |

| Leaders should harness the health and care workforce’s desire for addressing inequalities in society through equity-focused quality improvement | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

| Leaders should promote a culture of equity (providing care according to need) rather than equality (providing equal care to everyone) | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

| Health and care staff should acknowledge and take action where possible on the social determinants of health in QI initiatives | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ Low |

| Staff should be given adequate time, training and resources, especially culturally competent multilingual resources, to undertake equity-focused quality improvement | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Data should be routinely disaggregated by disadvantaged groups in all QI projects, for example by socioeconomic status and ethnicity | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, general practices with academic support | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| Staff should be supported to access data insights from the electronic patient record to support QI initiatives | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| QI initiatives should draw on qualitative and quantitative evidence to understand the experiences and barriers of disadvantaged groups | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| QI initiatives should be co-created and delivered in equal partnership with diverse patients and multidisciplinary staff groups | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

| QI initiatives should minimise the amount of effort required by patients to benefit as this is likely to increase inequalities | NHS England, ICBs, PCNs, Trusts, and general practices | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ Moderate |

*GRADE certainty communicates the strength of evidence for each recommendation.

Recommendations which are supported by large trials will be graded highest whereas those arising from small studies or transferable evidence will be graded lower. The grading should not be interpreted as priority for policy implementation – i.e. some recommendations may have a low GRADE rating but likely to make a substantial population impact.

How this brief was produced

Using AI-powered software called EPPI-Reviewer, the Health Equity Evidence Centre has developed a Living Evidence Map of what works to address health inequalities in primary care. The software identifies research articles that examine interventions to address inequalities. The evidence map contains systematic reviews, umbrella reviews. More information can be found on the Health Equity Evidence Centre website.

Funding

This Evidence Brief has been commissioned by NHS England to support their statutory responsibilities to deliver equitable health care and the evidence review draws upon the EQUAL-QI study which is funded by the NIHR Advanced Fellowship Programme. Policy interventions beyond health care services were not in scope. The content of this brief was produced independently by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NHS England.

Suggested citation

Ford J, Johnson L, Blythe J, Gajria C, Holyroyd I, Dehn Lunn A, Painter H, Pearce H. Evidence brief: What works – Leveraging Quality Improvement to address health and care inequalities. Health Equity Evidence Centre; 2025

References

- NHS England. National patient safety incident reports up to June 2022 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 9]

Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-patient-safety-incident-reports-up-to-june-2022/ - Hogan H, Healey F, Neale G, Thomson R, Vincent C, Black N. Preventable deaths due to problems in care in English acute hospitals: a retrospective case record review study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2012 Sep 1;21(9):737–45.

- Rea D, Griffiths S. Patient safety in primary care: incident reporting and significant event reviews in British general practice. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2016;24(4):411–9.

- Chauhan A, Walton M, Manias E, Walpola RL, Seale H, Latanik M, et al. The safety of health care for ethnic minority patients: a systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2020 Jul 8;19(1):118.

- Quality improvement made simple – The Health Foundation [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 9].

Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/quality-improvement-made-simple - Aqua [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 9]. Quality, service improvement and redesign (QSIR).

Available from: https://aqua.nhs.uk/qsir/ - Lynn J. The Ethics of Using Quality Improvement Methods in Health Care. Ann Intern Med. 2007 May 1;146(9):666.

- Reichman V, Brachio SS, Madu CR, Montoya-Williams D, Peña MM. Using rising tides to lift all boats: Equity-focused quality improvement as a tool to reduce neonatal health disparities. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2021 Feb 1;26(1):101198.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001.

- Bardach NS, Cabana MD. The Unintended Consequences of Quality Improvement. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009 Dec;21(6):10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283329937.

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. NPDA spotlight audit report on diabetes-related technologies 2017-18 [Internet]. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2019 [cited 2024 Mar 7].

Available from: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/npda_spotlight_report_tech_2019_final.pdf - Esan OB, Adjei NK, Saberian S, Christianson L, McHale P, Pennington A, et al. Mapping existing policy interventions to tackle ethnic health inequalities in maternal and neonatal health in England: A systematic scoping review with stakeholder engagement. Race and Health Observatory; 2022.

- McLintock K, Foy R, Canvin K, Bellass S, Hearty P, Wright N, et al. The quality of prison primary care: cross-sectional cluster-level analyses of prison healthcare data in the North of England. eClinicalMedicine [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Sep 9];63.

Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(23)00348-6/fulltext - Core20PLUS5 Programme. NHS England; 2021.

- Behling EM, Garris T, Blankenship V, Wagner S, Ramsey D, Davis R, et al. Improvement in Hypertension Control Among Adults Seen in Federally Qualified Health Center Clinics in the Stroke Belt: Implementing a Program with a Dashboard and Process Metrics. Health Equity. 2023 May;7(1):89–99.

- Burkitt KH, Rodriguez KL, Mor MK, Fine MJ, Clark WJ, Macpherson DS, et al. Evaluation of a collaborative VA network initiative to reduce racial disparities in blood pressure control among veterans with severe hypertension. Healthcare. 2021 Jun 1;8:100485.

- Cené CW, Halladay JR, Gizlice Z, Donahue KE, Cummings DM, Hinderliter A, et al. A multicomponent quality improvement intervention to improve blood pressure and reduce racial disparities in rural primary care practices. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2017;19(4):351–60.

- Cykert S, Eng E, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Heron DE, Jones NS, et al. A Multi-faceted Intervention Aimed at Black-White Disparities in the Treatment of Early Stage Cancers: The ACCURE Pragmatic Quality Improvement trial. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2020 Oct 1;112(5):468–77.

- Davidson C, Denning S, Thorp K, Tyer-Viola L, Belfort M, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, et al. Examining the effect of quality improvement initiatives on decreasing racial disparities in maternal morbidity. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022 Sep 1;31(9):670– 8.

- Main EK, Chang SC, Dhurjati R, Cape V, Profit J, Gould JB. Reduction in racial disparities in severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage in a large-scale quality improvement collaborative. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020 Jul 1;223(1):123.e1-123.e14.

- Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, et al. Improving Care for Minorities: Can Quality Improvement Interventions Improve Care and Outcomes For Depressed Minorities? Results of a Randomized, Controlled Trial. Health Services Research. 2003;38(2):613–30.

- Ngo VK, Asarnow JR, Lange J, Jaycox LH, Rea MM, Landon C, et al. Outcomes for Youths From Racial-Ethnic Minority Groups in a Quality Improvement Intervention for Depression Treatment. PS. 2009 Oct;60(10):1357–64.

- Parker MG, Burnham LA, Melvin P, Singh R, Lopera AM, Belfort MB, et al. Addressing Disparities in Mother’s Milk for VLBW Infants Through Statewide Quality Improvement. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 1;144(1):e20183809.

- Zhang R, Lee JY, Jean-Jacques M, Persell SD. Factors Influencing the Increasing Disparity in LDL Cholesterol Control Between White and Black Patients With Diabetes in a Context of Active Quality Improvement. Am J Med Qual. 2014 Jul;29(4):308–14.

- Hassaballa H, Ebekozien O, Ogimgbadero A, Williams, F, Schultz J, Hunter-Skidmore J, et al. Evaluation of a Diabetes Care Coordination Program for African- American Women Living in Public Housing. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 May 24];22(8).

Available from: https://www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal/article/146525/diabetes/evaluation-diabetes-care-coordination-program-african-american - Meurer J, Rohloff R, Rein L, Kanter I, Kotagiri N, Gundacker C, et al. Improving Child Development Screening: Implications for Professional Practice and Patient Equity. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:21501319211062676.

- Brown CM, Beck AF, Steuerwald W, Alexander E, Samaan ZM, Kahn RS, et al. Narrowing Care Gaps for Early Language Delay. Clinical Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;55(2):137– 44.

- Barceló NE, Lopez A, Tang L, Aguilera Nunez MG, Jones F, Miranda J, et al. Community Engagement and Planning versus Resources for Services for Implementing Depression Quality Improvement: Exploratory Analysis for Black and Latino Adults. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(2):277–86.

- Gagnon KW, Bifulco L, Robinson S, Furness B, Lentine D, Anderson D. Qualitative inquiry into barriers and facilitators to transforming primary care for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in US federally qualified health centres. BMJ Open. 2022 Feb 1;12(2):e055884.

- Matthews KC, White RS, Ewing J, Abramovitz SE, Kalish RB. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Cesarean Delivery: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Am J Perinatol. 2022 Aug 22;s-0042-1754405.

- Olsson E, Lau M, Lifvergren S, Chakhunashvili A. Community collaboration to increase foreign-born women´s participation in a cervical cancer screening program in Sweden: a quality improvement project. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2014 Aug 9;13(1):62.

- Greenwood PJ, Shiers DE. Don’t just screen intervene; a quality improvement initiative to improve physical health screening of young people experiencing severe mental illness. Mental Health Review Journal. 2016 Mar 14;21(1):48– 60.

- Watanabe MK, Hostetler JT, Patel YM, Dios JMV de, Bernardo MA, Foley ME. The Impact of Risk-Based Care on Early Childhood and Youth Populations. Journal of the California Dental Association. 2016 Jun 1;44(6):367–77.

- Green S, Beveridge E, Evans L, Trite J, Jayacodi S, Evered R, et al. Implementing guidelines on physical health in the acute mental health setting: a quality improvement approach. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2018 Jan 10;12(1):1.

- Furness BW, Goldhammer H, Montalvo W, Gagnon K, Bifulco L, Lentine D, et al. Transforming Primary Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: A Collaborative Quality Improvement Initiative. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2020 Jul 1;18(4):292–302.